The Saints of Little Portugal

July 19, 2017 | #toronto #portugal #art

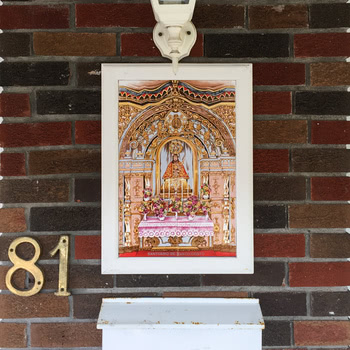

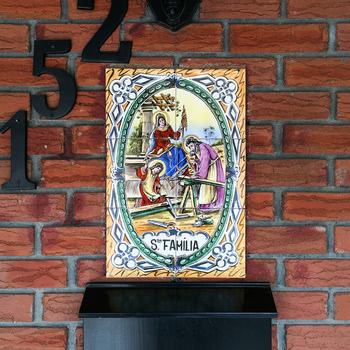

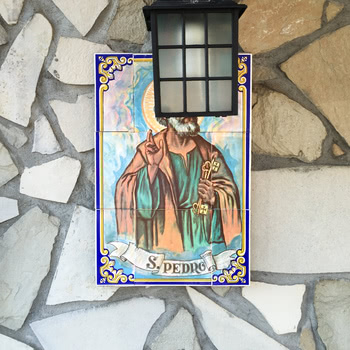

When you next walk through the residential streets of Toronto's west end, take a look at the houses around you. Before long, you'll see the azulejos.

Carefully glued by a house's front entrance, azulejos are small sets of ceramic tiles, usually six or twelve per panel. Though each panel typically depicts generic-looking Catholic iconography - various iterations of the Virgin, miscellaneous saints - they're effectively ethnic markers:

To see one is to know that the owners are Portuguese immigrants.

In May 2015, I canvassed my neighbourhood, from Ossington to Dufferin and from Queen to Dundas, and catalogued every azulejo I found: sixty six of them in total.

Slightly more than what meets the eye

You can be certain the owners are Portuguese for two reasons.

First, the azulejo is a distinctively Portuguese art form, though they're also common in Spain and in the former colonies.

Both the word 'azulejo' (which refers to any ceramic tile) and its artistic tradition were introduced by the Moorish invaders, who brought with them their Arabesque decorative ceramics and an obsession with filling empty space.

Adopted first in Spain, in the 1500s they were imported to Portugal. In the 1600s their manufacturing was improved by the Dutch, and they became widely used by the 1700s. Many houses in Portugal today are still covered top to bottom, inside and out, in azulejos: they're cheap, they last forever, they're easy to clean, and they keep things cool in the summer.

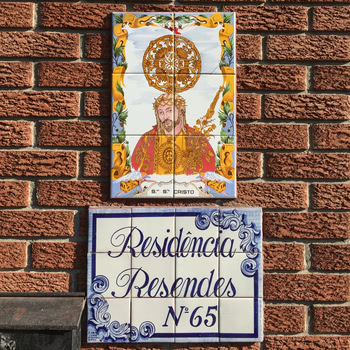

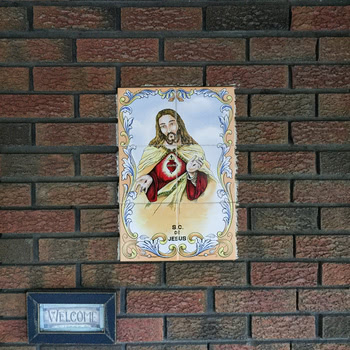

Secondly, these azulejos feature Portuguese saints.

If to glance at an azulejo is to have a suspicion, then to see the tortured face of Senhor Santo Cristo dos Milagres (Lord Holy Christ of The Miracles) is to know that the owners are, specifically, from the Açores.

I don't quite recall all the theological quirks,1 but, in a nutshell, Catholics love their minor cults.

You may only worship the Holy Trinity, of course.

But if you're in a jam and need a favour, it's common to pray directly to a holy-adjacent figure that specializes in your troubles. Cults form around specific divine interventions and become embodied by a stable iconography laden with symbolism. Choosing a saint or figure in particular often reflects traditions from your family or region.

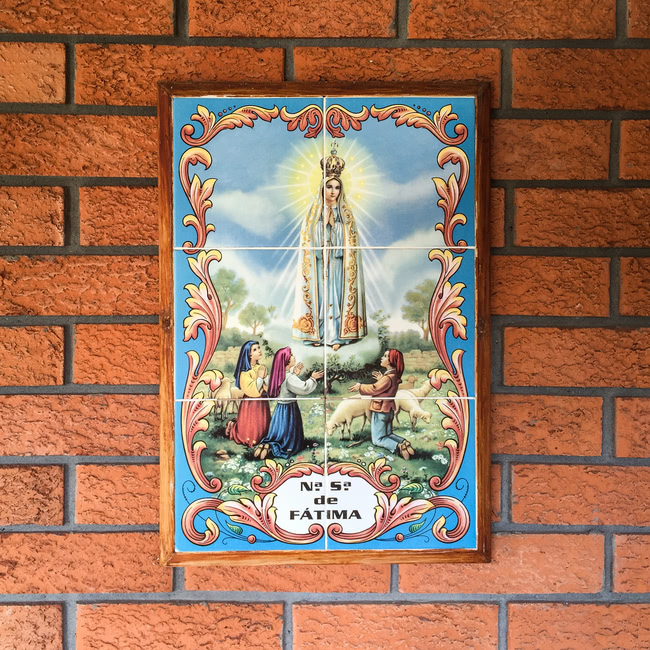

Take Nossa Senhora de Fátima.

In 1917, Our Lady the Virgin Mary appeared2 to, and hung out with, three little shepherds3 in the village of Fátima. She did this six times over the course of several months and, before she left for good, she gave the shepherds three secrets and performed some miracles. People were so impressed, they built an immense sanctuary right on the spot.

Today, it receives millions of tourists every year. People in need will make pilgrimages and, in penance, crawl on their knees the whole way there.

I grew up about a ten minute drive from Fátima. I went to school there. I've attended mass both in the cathedral, and outside, during high season, when tens of thousands of pilgrims congregate in the sanctuary grounds. For me personally, it's all extremely normal, a kind of background cosmic religious radiation.4

Most Portuguese immigrants to Toronto, though, are not from the mainland — let alone from my region.

Last fall, while en route to work, I noticed that the church down on Argyle and Dovercourt was unusually crowded for a Thursday morning. I stopped an old man and asked him, is this a funeral, a wedding or what? With emotion in his voice, he replied: they brought Our Lady over! and beckoned me to check it out.

I parked my bike, and stepped inside the church. The pews were packed with worshippers, and a priest was wrapping up a mass. I spotted her, in the distance: there stood the pilgrim image of Our Lady of Fátima. I chatted with an old lady who told me she never thought she'd get to see it in the flesh; she seemed very pleased. I later found out that the statue was making a week-long tour of the Greater Toronto Area Portuguese churches.

While Fátima is the most famous... visit by Our Lady,5 the Lord works in mysterious ways. Over the centuries every other town has had a holy appearance or become associated with a given saint. Saint Anthony represents both Portugal and Lisbon, and helps with marriages, the poor, and finding things that are lost. Saint Joseph, in turn, is the patron saint of fathers, families and Canada.

Stocks and flows

Most Portuguese came to Canada in the 1960s and 1970s,6 and largely settled in Montreal and Toronto. By the time I was born, my ethnic group consisted of up to one third of the population in Toronto's west-end neighbourhoods.7 People fled the subsistence farming, crushing poverty and fascist political repression that at the time was a constant in the home country.

Most first-generation immigrants are from my parents' and grandparents' generation, though, and what used to be a bustling ethnic enclave has since petered out. Between the reduced rate of migration and the unsustainable housing inflation that is fuelling our housing crisis,8 the old people who remain are dying or selling out and are being replaced, as far as I can tell, by wealthier "ingleses".

When I first began this project, I was engaging in a kind of proactive nostalgia: I was moving to California for a few months, and I felt sad about missing summer in Toronto. I didn't realize at the time that I was also creating a record of gentrification.

Cities change, it's how it goes.

As I write this, I am being evicted myself from the neighbourhood: my landlords cashed in and sold the house I live in — which is now being converted into luxury rentals. I'm currently looking for housing, but odds are good I won't be able to stick around.

I've lived in or adjacent to Little Portugal for about seven years now, and for a long time I got to have it both ways: I was both gentrified and gentrifier. On the one hand, I frequented the bakeries, the bbq shops and rather enjoyed doing all of my shopping without speaking English.9 On the other hand, I also got to live in what was hipster-central and hang out at all the nice new bars and restaurants.

I'm not sure that I have a special right, per se, to stay in this specific neighbourhood. But there's something to be said about all the different amenities10 and quirks that mostly only people like me can enjoy, and that will vanish without enough people like me to support it.

Put another way: enjoy it while it lasts!

-

At the end of every year, the priest would come down from the castle (i.e. the parish headquarters) and quiz the kids on their bible lessons. What are the seven deadly sins? What were the three temptations of Christ? When I was thirteen I skipped out on the oral examination to go on summer vacation early, and upon my return I was informed I had flunked Sunday school. My faith was already unsteady, but I decided right then and there that organized religion wasn't my thing. ↩

-

Think less "showed up" and more "apparation". ↩

-

Think less "picturesque" and more "child labour". The oldest was ten, and this being deep rural Portugal, they were very likely done school forever, if they had any schooling at all. It's hard to overstate how little education people received. By the time I finished highschool, I had more years of formal education than all four of my grandparents put together. ↩

-

I worked on this essay for several days before I realized that I'm not immune: I own a tiny, glow in the dark Our Lady of Fátima figurine. It was too tacky not to purchase. ↩

-

You may have heard of many other Our Ladies, including but not limited to: Hope, Mercy, Lourdes, Guadalupe, etc. These all refer to the one and only Virgin Mary, and are either specific titles attributed to her, or are specific locations where she has appeared. I added this footnote because this was apparently not obvious, which is very amusing to me. ↩

-

Before the 1950s, like many other ethnicities and nationalities, the Portuguese were considered to be "undesirable", incapable of adapting to Canadian farming conditions. After 1974, between the end of the dictatorship (which ended the colonial wars and eased material deprivation) and the new Canadian points-based immigration system (which deprioritized unskilled labour) the flow of Portuguese slowed to a trickle. ↩

-

There is a great, illustrative audiotour guide you can follow along here.↩

-

I have lots of feelings about this, as you may guess. I've started a group named BetterToronto and you should check it out. ↩

-

I've had the following weekend routine for many years now: walk on over to the laundromat, cross the street for lunch at the churrasqueira, fetch bread and a pastel de nata at the bakery, circle around to obtain chouriço and queijo fresco from the butcher. There's only one or two other areas in this city where you can replicate this experience. ↩

-

"Amenity" I think is a bit loaded; imagine calling it "infrastructure". Immigrant enclaves are actually very important for recent newcomers: when you're fresh off the boat, you depend heavily on the community for jobs, for housing, for social interaction, for learning how to navigate society around you. We don't just lose "quaintness" when an enclave gets eroded away. ↩