Actually, Rent Control Is Great

November 13, 2017 | #housing

A version of this article was published in the Toronto Star. Interested in learning more? You can read the full paper here.

I’ve been renting in Toronto for almost a decade now, and I’ve watched rents in my neighbourhood(s) climb substantially. In that period I have moved eight times, and whenever I have looked for housing the uncertainty of living in an uncontrolled apartment weighed heavily on my mind. That’s why I got excited when, back in April of this year, the government of Ontario announced that it was extending rent control to every dwelling in the province, as opposed to just buildings constructed before 1991.

However, this move prompted a lot of commentary, and the chorus was overwhelmingly negative. Critics argued that, under rent control, the quantity and quality of available rental units will fall as developers are less incentivized to build rental properties, and that the province should instead tackle the root of the problem: the supply of new housing is not keeping up with demand.

To me this was strange, since removing the exemption seemed like such a no-brainer. And, much to my disappointment, few if any critics actually addressed what I felt was the real problem at hand: the lack of security of tenure. This prompted me to look into the research.

Housing insecurity means you have to move all the time, which is expensive, but the real cost is in the instability it inflicts. The constant possibility of eviction, two months’ notice, changes your relationship with the community around you. If your stay is likely to be short, then volunteering at your local school or investing in strong local ties doesn’t make a lot of sense. Quite the opposite: it may well be in your interest that your community not improve or appreciate too much. A brand new transit line or community centre that causes the cost of your home to exceed your resources and forces you to move is no cause for celebration.

Studies have found that being a homeowner, as opposed to a tenant, means you live longer and are both physically and psychologically healthier. It makes you less likely to retire early due to health reasons and homeowners on average spend less time unemployed. Owners live in neighbourhoods with lower crime rates, and their children are less likely to suffer from depression, and are more likely to graduate from high school. These effects persist even after controlling for wealth and income, but tend to go away when we control for residential stability. Since we spend many times more money subsidizing homeownership than we do helping tenants, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that we deliberately impose these externalities on renters.

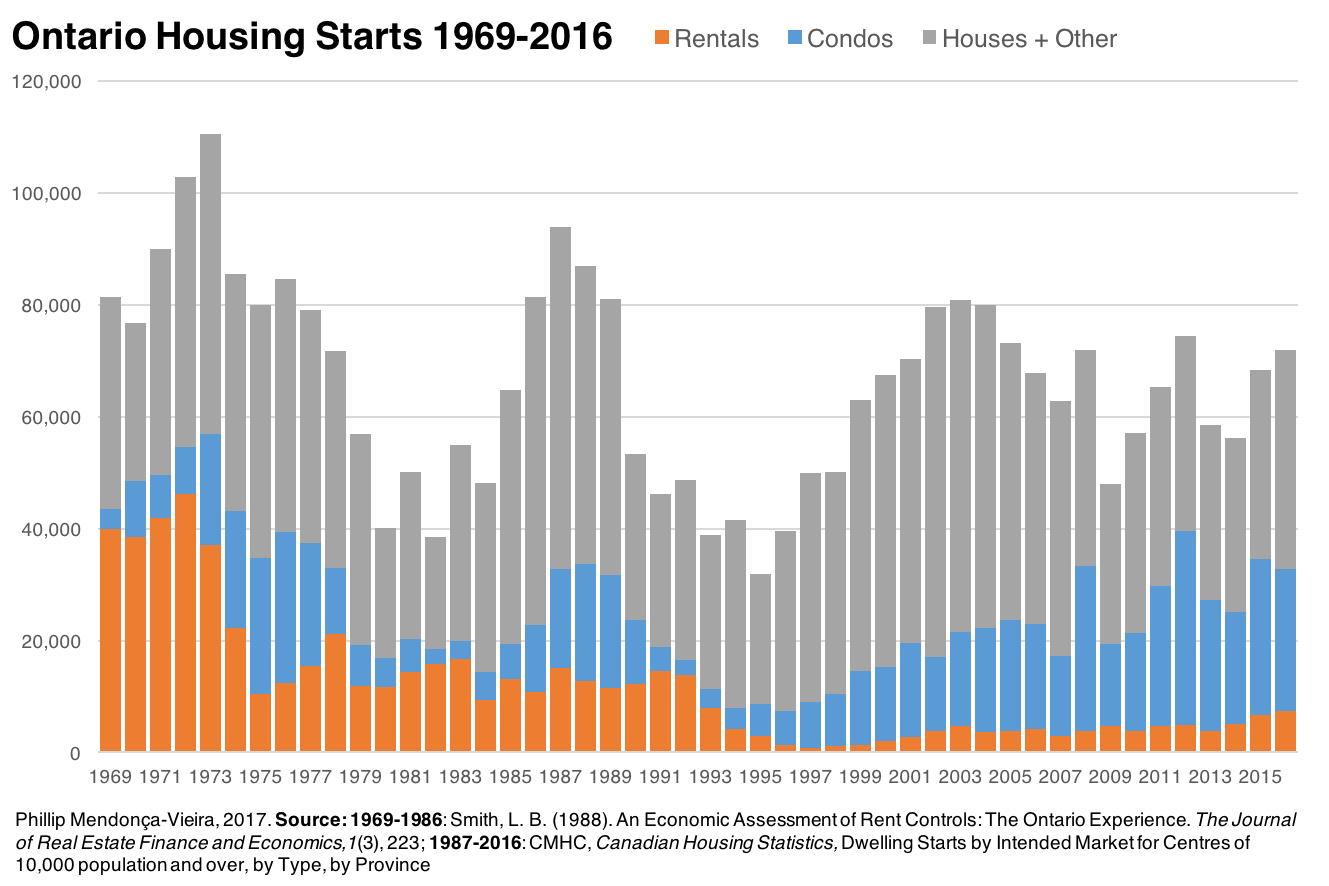

Meanwhile, data shows that Ontario’s rent controls do not actually have the pernicious effect on the supply of new rental housing that is attributed to them. Consider that rent control in new buildings was permanently exempted back in 1998 — yet rental housing starts have failed to recover, and today we build far less rental housing than we did in the 1970s and 1980s. While a strict price control that causes real costs to rise above real incomes is indeed harmful, that does not accurately describe the kind of rent control we have in Ontario. A well designed control, one that allows rents to rise with costs and inflation, does not actually harm new supply, and this is corroborated by researchers that examined controls similar to ours in Manitoba, New Jersey and Massachusetts.

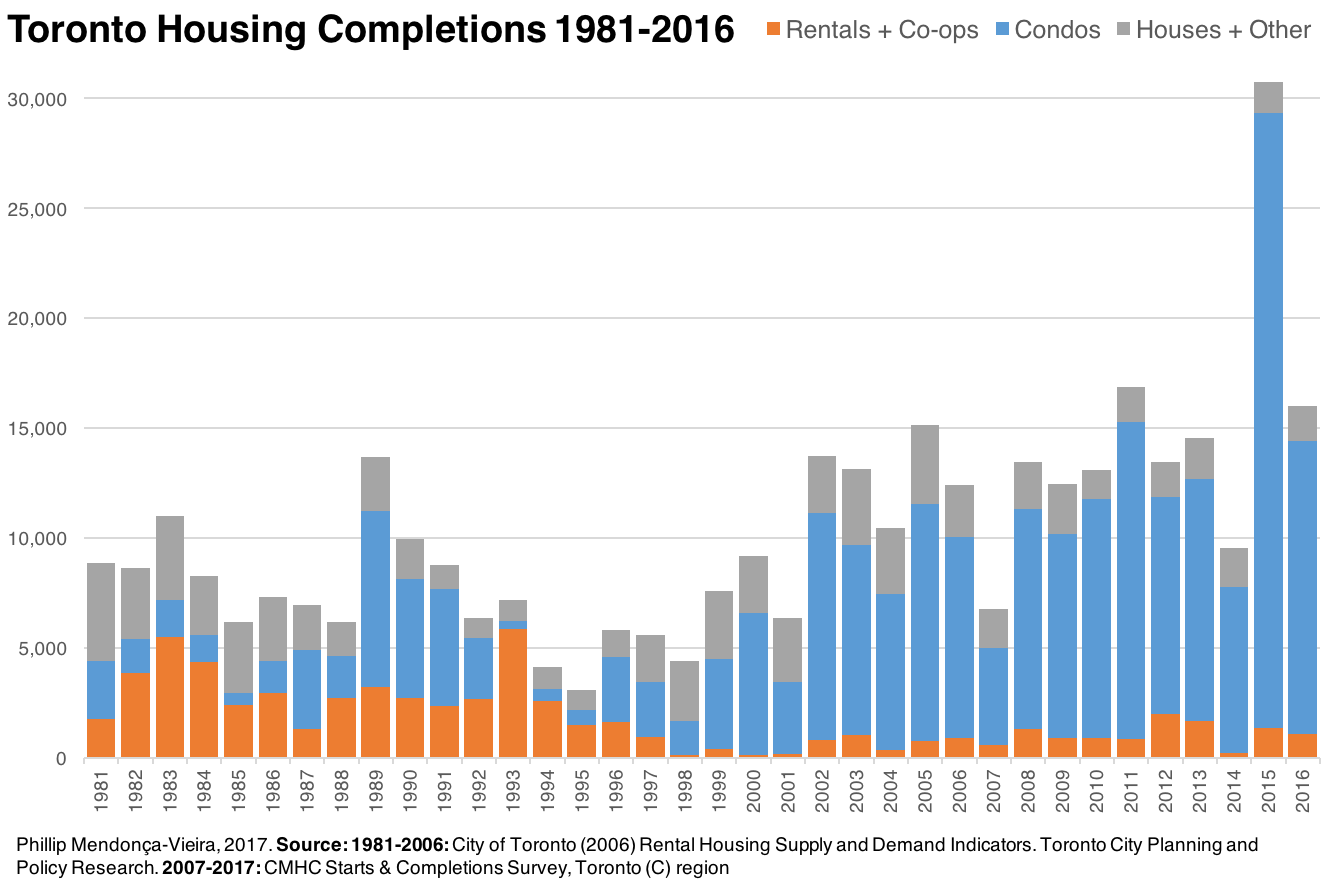

A more likely explanation for the squeezing of our primary rental housing supply in recent decades can be found in the legalization of condos, in 1967, and the federal government’s overhaul of our tax system in 1972 and other changes in subsequent years. Prior to the Condominium Act all apartment buildings were rentals, since title could not be sold for individual units. And prior to the revisions of the Income Tax Act rental buildings were attractive tax shelters for high income individuals looking for stable returns on their investment. Since today building to own is less risky and more profitable than building to rent, in practice condominiums have crowded out investment in rental buildings. Their impact is easy to see in Toronto’s housing statistics.

Commentators do us a disservice when they pretend rent controls are about affordability or redistribution and ignore tenant concerns over security of tenure. From what I’ve learned it’s way more complicated than that. Today, low- and middle-income people have been priced out of ownership in our city. Why should we be subjected to a tenancy regime that significantly disadvantages us socially, economically and politically compared to the subsidized homeowning population?