Actually, Rent Control is Great: Revisiting Ontario’s Experience, the Supply of Housing, and Security of Tenure

September 26, 2018 | #housing

This paper is also available in pdf form.

Abstract

Rent controls are criticized for acting as a severe disincentive to new and existing rental construction. From 1992 to 2017, the province of Ontario exempted all new buildings from its rent control regime. What was the effect on rental construction in Ontario during that time period? Finding that rental construction continues to be depressed, this paper documents contemporary Canadian housing policy initiatives and investigates the theoretical and empirical record of rent controls in other jurisdictions. This paper then argues that rent controls’ most important aspect is their regulation of the provision of security of tenure – which should be seen as a right of tenants as well as homeowners.

Keywords: rent control, security of tenure, housing, Ontario, Canada

This research was conducted independently during the fall of 2017 and was funded by the author’s personal savings. The author can be reached at phillmv -at- okayfail.com

Contents

- Introduction

- Rent control in Ontario

- Revisiting Ontario’s experience

- A theoretical overview

- The role of security of tenure

- Conclusions

- Tables

- References and footnotes

Introduction

In April 2017, the government of Ontario decided to extend rent control to every rental unit in the province, as opposed to just those in buildings constructed before 1991.

Different jurisdictions have overlapping definitions of “rent control”. What Ontario engages in is described by some academics and regions as a tenancy rent control, or as rent stabilization. It works like this: once a year, a landlord can raise the monthly rent by a provincial guideline pegged to inflation, or inflation plus 3% if their costs have spiked or they made improvements to the unit. Between tenants, landlords are free to price rents at whatever the market will bear.1

This prompted a lot of commentary, ranging from benign skepticism2 to vigorous condemnation.3 The chorus sounded like this:

Against all common sense, the province is handing its cities a poisoned chalice: it is textbook economics that price controls sharply reduce the value of new construction.4 Under rent control, the quantity and quality of available rental units will fall as developers are less incentivized to build or invest in rental properties — all of which exacerbates any price crunch.5 The fact is, rent control would largely help high-end renters in a high-end market, since most units built after the rent control exemption are condominiums. It’s tough to see how rent control would accomplish much except transferring money from unit owners to their tenants.6 Instead, the province should be tackling the root of the problem: the supply of new housing units in Toronto and elsewhere is not keeping up with demand.7

As a casual observer and experienced tenant, these claims seemed a little counter-intuitive. Toronto is currently in the grips of a housing crisis. A speculative real estate bubble has priced out ownership for low- and middle-income people,8 and it’s easy to find stories about sitting tenants seeing their rents jump by hundreds of dollars.9 10 11 Every time I have looked for housing, the uncertainty of living in an uncontrolled apartment weighed heavily on my mind.

When demand for rental units is high and vacancy rates are low, landlords have a lot of power over their tenants — and all the more if they can increase rents at will. The absence of controls allows the unscrupulous to evict tenants exercising their rights, and the eager to extract more for the same service they provided before. It seemed strange for so many critics to ignore what felt like the real problem at hand: the lack of security of tenure. Could rent controls really be that counterproductive? For that reason, I decided to learn as much as I could about the topic.

This paper explores the mechanics and outcomes of rent control policies. First, I examine the empirical evidence of rent control’s impact on rental housing construction in Toronto and the province of Ontario over the past forty years. Then, I review the economics literature and explore and challenge the theoretical basis for rent controls’ poor reputation. Finally, I examine our shifting understanding of the relationship between tenants and landlords, and the history of Canadian housing policy to argue for the state’s role in ensuring the provision of security of tenure.

Rent control in Ontario

During the 1970s and 1980s

When we talk about rental supply, we typically distinguish between the “primary” rental market, where professional landlords operate purpose built rental buildings, and the “secondary” rental market, where individuals rent out their basement apartments or spare condominiums.12 We typically favour primary rentals because professional, full-time landlords are more capable of absorbing maintenance costs and are far likelier to provide long-term accommodation. Condominium units have a tendency to get flipped, and basement apartments are often vacated for the owner’s own use.

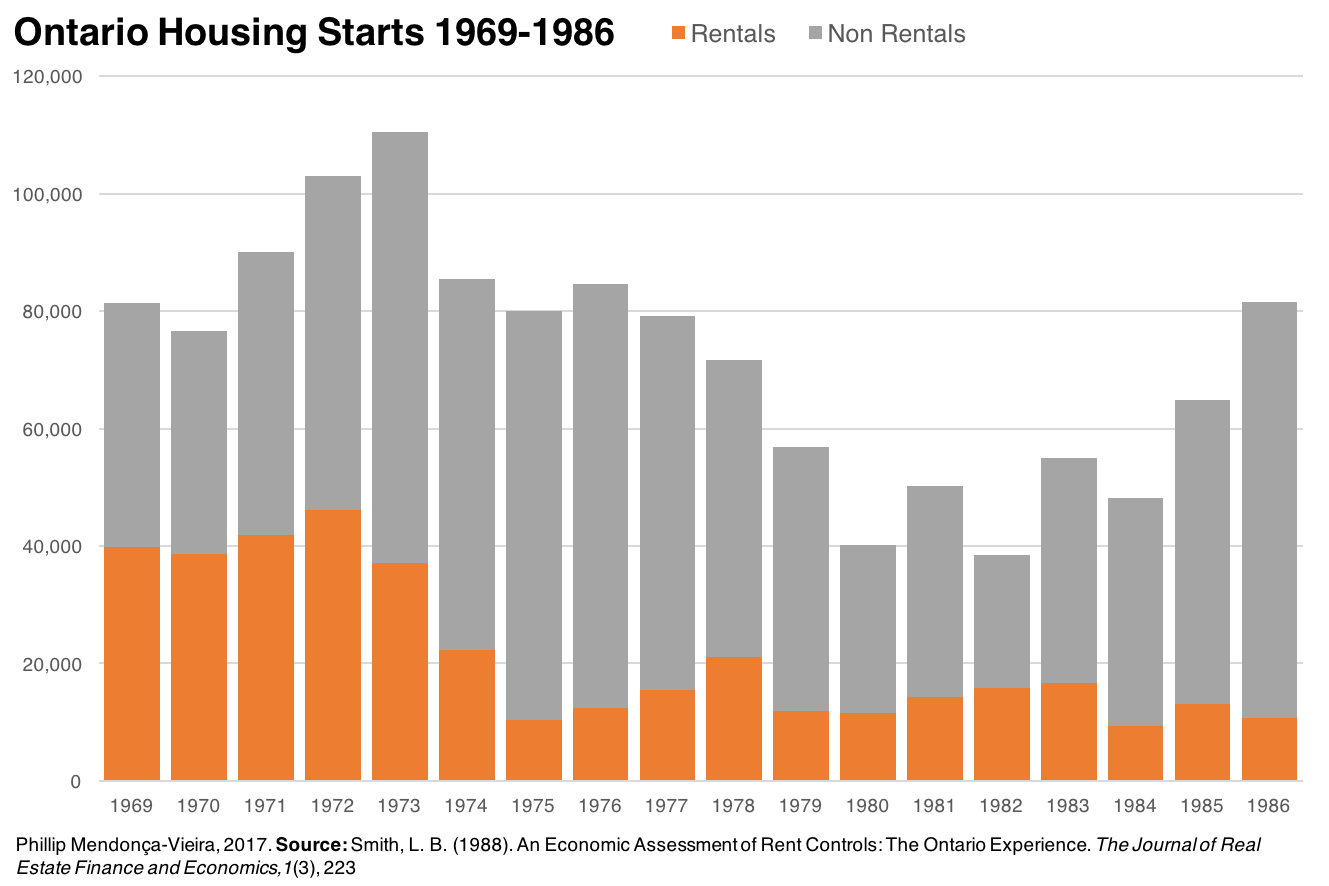

We’re blessed that Ontario is a relatively well studied jurisdiction. In a widely cited13 paper written in 1988, Lawrence Smith looked at Ontario’s rental market in the aftermath of the province’s rent controls.

According to Smith, the primary rental housing sector has been in a state of crisis for about forty years.14 Beginning in the 1970s, the construction of new private purpose-built rental buildings collapsed. If in 1969 Ontario had 27,543 new, unassisted rental building starts, by the mid 1980s under 5,000 were being built as private developers left the market.15 At first their departure was compensated by government assisted housing starts, but before long the provincial and federal governments began to withdraw funding as well.12

Around the same time primary rentals dried up, new tenant protection legislation was being introduced, and by 1975 rent controls were in effect throughout the province. In the beginning, rents were essentially fixed in nominal terms, which in a high inflation era meant their real values quickly declined. New construction was at first exempted, and then not; only by 1986 were the guidelines changed such that rent adjustments became tied to inflation.15

Smith’s technical argument against controls goes something like this: rent control artificially lowers the income that landlords can expect to receive from rental properties. This depresses any motivation investors may have for responding to demand by creating new rental buildings. Meanwhile, lower rent costs relative to ownership encourage more people to stay in the rental market, which creates more demand for fewer units. A control imposed in response to unaffordable rents and low vacancy rates will therefore exacerbate both.

Rent controls don’t just affect new construction, and therefore new tenants; they can have stark effects on existing units as well. Faced with a control where increases in rent grow at a rate slower than the costs of maintaining the property, existing landlords are strongly encouraged to let their properties deteriorate, or convert them to condominiums.

Smith argued that all of the above occurred after the province instituted its 1975 rent controls. He found that real rents and capital values of rental units collapsed, and that Toronto lost 11% of its moderately priced rental housing stock through conversions, demolition, and eviction through renovation. By 1986, vacancy rates were an extremely low 0.1%, but the market was unable to add supply. To quote:

In a normally functioning, uncontrolled housing market a vacancy rate below the natural (or equilibrium) rate triggers an increase in real rents and real capital values. This in turn stimulates increased expenditures on the existing stock and increased new construction. Rent controls break this connection between low vacancies and large housing expenditures, and thereby impede the market adjustment necessary to satisfy the excess demand.

…

The timing and severity of the decline in rental housing starts, especially in government unassisted rental starts, and the contrast with the pattern of single detached, semi-detached and duplex starts suggest rent controls substantially reduced the volume of new rental construction in Ontario.

[Other factors such as less favourable demographics, rising interest rates, and increased tenant protection may have exacerbated the decline in rental starts, but rent controls appear to be the primary factor.] 15

Revisiting Ontario’s experience

During the 1990s and 2000s

Let’s take this for granted, then. Rent controls appear to be the primary factor. Smith’s paper was published some time ago. What has happened since?

In 1992, the New Democratic government’s Rent Control Act limited the kind of capital expenditures landlords could recover via rent increases and once again exempted new rental housing from rent control for a period of 5 years.16 In 1998, the Progressive Conservative government initiated the most dramatic change since their introduction: capital expenditures could now be fully recovered, vacancy decontrol17 was introduced for existing units, and rents in new buildings were permanently deregulated.18 19

This means that for over twenty years20 tenants have lived in a regime where new construction lacked any kind of rent control. If rent controls by themselves are the main disincentive acting on the volume of new rental construction, how do we expect the market to have responded since?

Any recent resident of Toronto can attest to a rapid pace of new construction. My assumption was that, starting from 1998, we should see a slow but steady increase in the rate of construction in new rental buildings and that they should eventually reach levels similar to those pre-1975.

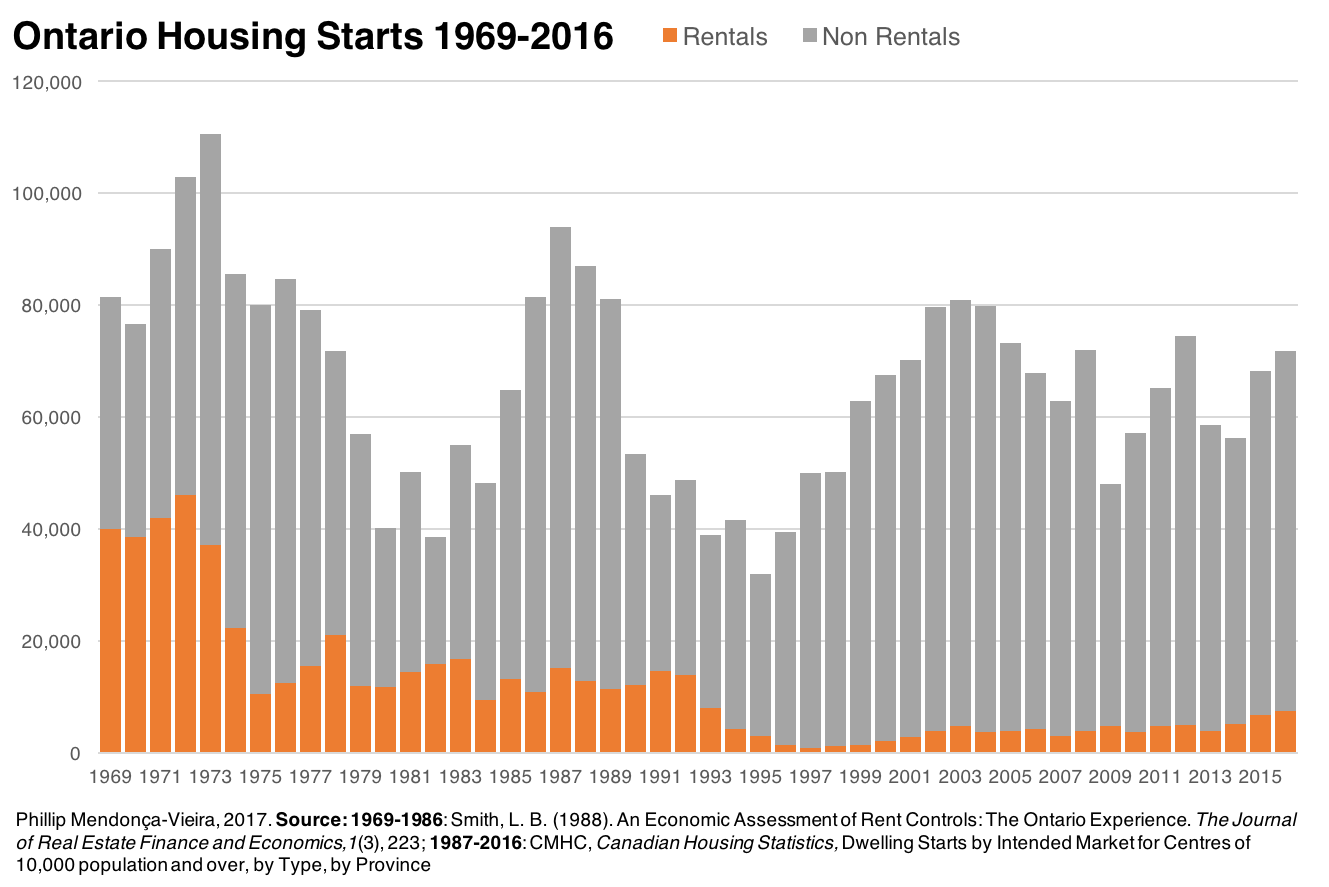

Compiling data provided by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), I was able to extend Figure 1 up to the present day:

During the 1969-1974 pre-rent control period for which we have data, there were on average 32,704 unassisted rental starts per year, or about 30% of total production. From 2009 to 2016, a period without any rent controls, Ontario averaged 5,147 new rental unit starts, or a mere 10% of total supply.

If rent controls were the primary factor inhibiting new construction today, then surely we’d expect to see the opposite. Yet primary rental starts remain depressed. Opponents of controls argue that developers continued to price in the risk of their reintroduction,21 but judged over the course of almost a generation that argument is wanting.

One downside of Smith’s 1988 study is that it does not control for demographics, interest rates, recessions, etc. Rent controls could have caused record low vacancy rates by inducing higher demand – but 1986 was also when the majority of the baby-boom cohort hit the prime rental occupancy age range of 20-35.22 Adequately controlling for everything is no easy task: reviewing the literature, it’s a bit of an open question whether we possess the empirical data or theoretical capacity to do so properly.23

It’s unsatisfying to merely note that the existing hypothesis doesn’t fit new data. Ideally, we should be able to supply our own causal narrative. Why have developers built fewer units than they did during a period of harsh rent control? For that matter, why aren’t they building them like they used to in the 1960s?

What else could be happening? While researching housing policy and statistics, I was able to identify two other big shifts that significantly impacted our housing supply.

The rise of the condominium

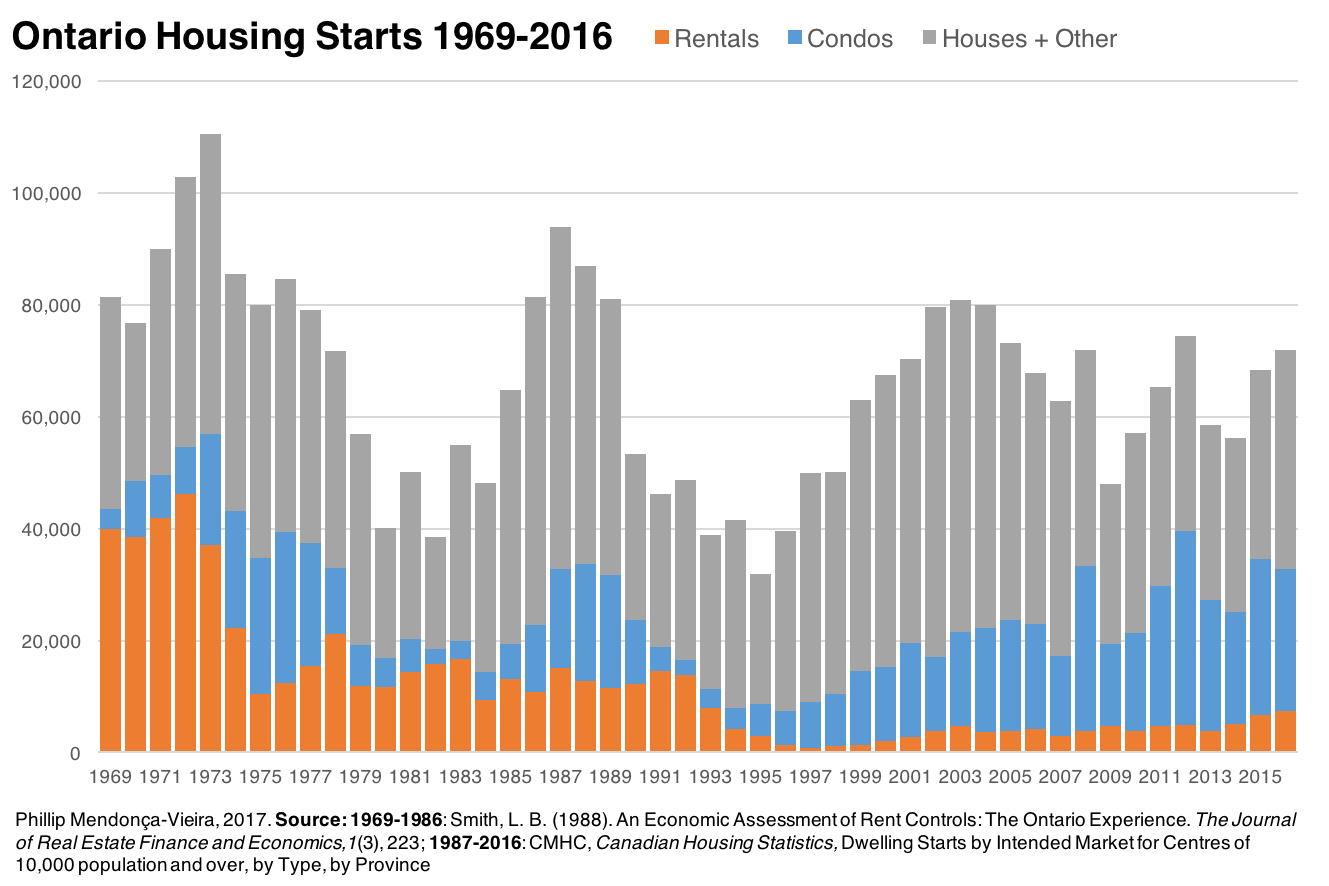

The first shift happened in 1967, when Ontario legalized condominiums and created a new form of property ownership – thereby substantially altering the economics behind multi-residential buildings. Since then, condominiums have dominated multi-residential construction.

This trend stands out pretty clearly when condominiums are compared to rentals:

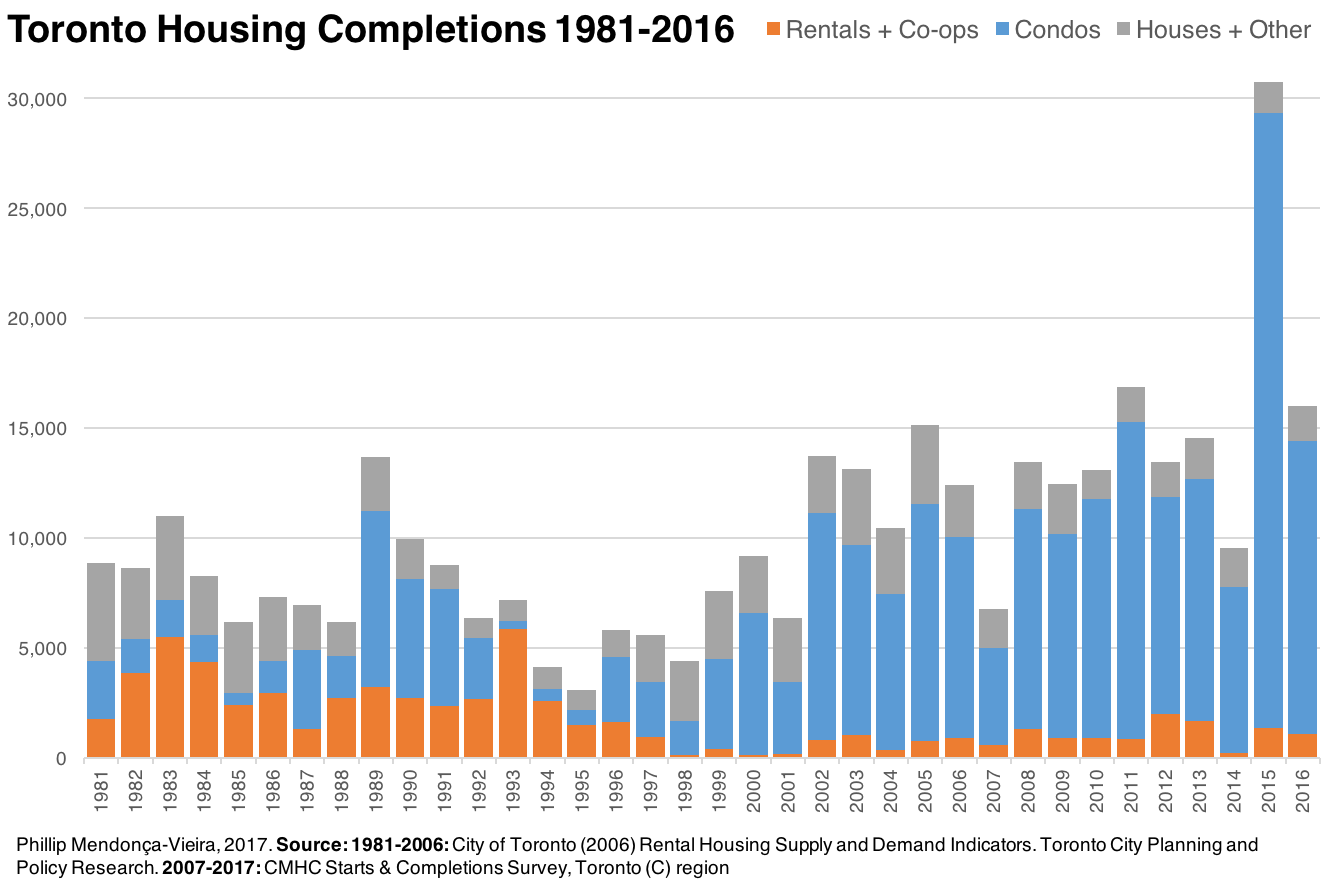

On second thought, I wondered whether looking at this data at a regional level might be misleading, since different sub-regional housing markets have differing economic conditions. As you can see from the housing mix in Figure 3, Ontario was and still is aggressively subdividing and sprawling. With an abundance of available freehold land it’s possible that, looking at province-wide data, we might understate the impact of condominiums. How would this look like in an already built-up area where by and large higher density developments are the only option?

For that reason, I dug up and plotted recent and historical data from Toronto:26

Prior to the Condominium Act, apartment buildings could only be rented out or sold in their entirety. Now, for the first time, title could be given to each individual unit, greatly increasing the allowed density of privately owned housing. Condominiums immediately began to crowd out rental building investment: the first condominium in Ontario was originally constructed as a rental and was converted to a condominium soon after the law came into effect.27

Why is that so? In 2012, Jill Black wrote a great research paper regarding the financing and economics of multi-residential housing development. She explores the incentives property developers act on and the disincentives they suffer as they choose projects to work on, and it’s well worth a read. According to her research, building to rent is riskier and less profitable than building to sell.28

Developers find building for the ownership market more attractive because with condominium projects construction doesn’t begin until a majority of units are pre-sold to qualified buyers. This early-on cash stream reduces the amount of necessary debt, lowers interest repayment costs, and makes it easier to obtain financing. By the time the condominium units are occupied, the developer has realized their returns and freed up their equity for use in other projects.29

In contrast, a rental building doesn’t generate income until it’s completed and therefore it’s harder to assess and demonstrate its financial feasibility. This means more equity is needed to obtain more expensive, CMHC insured, financing – equity which won’t be recouped for years or decades.29 Land values, which account for 15-30% of the cost, are thus driven by the more profitable condominium projects.30 In a way, the development of condominiums in desirable locations can lead to a kind of “Dutch disease”, whereby the more profitable projects support an increase in costs and prices that make other, lower margin, projects unprofitable by comparison.31

Finally, registering as a condominium allows for a more favourable tax treatment, since multi-residential properties are discriminated against by both our sales tax regime32 and by municipal property tax rates which are set higher than ownership housing.33 The average tenant in Ontario pays twice the property tax rate of a homeowner, which for a hypothetical new rental building in Toronto works out to over $200 a month in rent per tenant.34

However, condominiums didn’t just change supply incentives. They also changed demand. Ownership has several advantages compared to renting: a homeowner has more control over their surroundings, an easier time accumulating wealth, enjoys tax benefits (which I will soon discuss), and so on. By expanding the options for ownership, condominiums remove the highest income earners from the rental market. As a consequence, “there has been a significant fall in the demand for private renting amongst those able to pay the rents needed to generate new construction of private rented housing” and renting has increasingly become the domain of people with lower incomes.36

All of this conspires to make profit margins in the multi-residential investment market very narrow. What might be a suitable rate of return for an insurance company looking to operate a rental building is often insufficient for a developer to build a new one.33 Small shifts in financing terms, land values, costs incurred due to delays in the regulatory planning process, and taxation can have a serious impact on the feasibility of a given project.

The notion that condominiums crowded out rental investment is compelling, but by itself doesn’t really exculpate rent controls. What if controls are just enough of a disincentive to shift the equilibrium?

The end of real estate tax shelters

The other significant event occurred in 1972, when the federal government overhauled the income tax system. Seeking to make taxation more equitable, close loopholes and reorient which industries it incentivized,37 starting in 1972 and throughout the 1970s and 80s, the federal government implemented a series of reforms.

For the first time, the government began to tax capital gains – with the notable exception of the sale of a primary residence. The government changed the tax treatment of losses due to capital cost allowances, the rate at which capital costs can be depreciated, and removed the ability to pool rental buildings and defer the recapture of depreciation upon the sale of a property. It also prevented investors from outside the real estate business from claiming capital cost deductions or offsetting income via rental losses, and it altered how and which “soft” construction costs like architect fees, building permits, etc, can be deducted,33 amongst other changes.38 39 16

In practical terms, this meant that purpose-built rental buildings became a far less attractive investment class, while homeownership became far more attractive. Taxing all capital gains except primary residences, in addition to the variety of demand and supply side incentives and subsidies being offered at the time, is a considerable enticement for diverting money into homeownership. With regard to rentals, being able to depreciate a building tax-wise at a faster rate than its actual economic depreciation can have a large impact on after-tax returns.33 Rental buildings become more profitable over time, as inflation and debt repayment lowers ongoing operating costs; prior to these reforms, high-earning professionals could use losses generated by rental properties to offset their higher marginal tax rates, and they could use liberal capital cost allowance rates to defer income tax until they sold their property.16

Additionally, in 1991 the Goods and Services Tax was introduced (and later, harmonized in most provinces), which increased the sales tax burden on new construction by almost 70%.40 Whereas before only the building materials used in the construction of a rental building had a sales tax, now the full value of the building was subject to a 7% charge (though, lower today).41 Renters don’t pay GST/HST on their rent, which means that developers are stuck with input credits they can’t use, thereby “stranding” tax costs.35

Marion Steele, writing in 1993, argued that these reforms, coupled with contemporary macro economic conditions, incentivized small scale landlording. The 1970s and 1980s featured high inflation and unprecedented housing price booms, which made expected capitals gains “the dominating motivation of investors”. Capital gains, in turn, are more valuable to high-income individuals than they are to corporations, whose marginal tax rates are lower.42 Before, developers built large scale schemes for their own investment, and smaller schemes for sale to high-income individuals or their syndicates. But now these tax changes prompted developers to leave the industry,43 and drew investors to dwelling structures that were easier to sell and whose conversion to ownership tenure was unrestricted: houses, duplexes, etc, and condominium units.42

These changes were made with little, if any, regard for their adverse consequences for our housing policy goals,39 and given that the “Great Apartment Boom” of the 1960s ended shortly thereafter suggests that the effect of these changes was substantial.16

Various federal Liberal governments recognized there were consequences from changing the Income Tax Act and tried to do something about it. The Multi-Unit Residential Building incentive (1974-1979, 1981) re-enabled the use of rental investment as a tax shelter. The Assisted Rental Program (1974-1979, 1981) gave subsidized mortgages to developers in exchange for below-market rents. The Canada Rental Supply Program (1981-1984) provided interest-free loans for up to fifteen years. The list goes on.44 45

Besides the decline in rental housing starts, we have one other piece of evidence: the United States’ current tax regime as applied to rental buildings is broadly similar to how we did things pre-1972.46 Though we can’t compare them directly – Canada and the US are very different places – consider the example of Seattle and Vancouver. While Vancouver is experiencing a furious condominium boom, taking up to 60% of housing starts, the vast majority of new units in Seattle are apartment buildings.47 48

In review

Commentators argue that rent controls are harmful because they remove new primary rental supply from the market, and therefore exacerbate the problem of low vacancies. In 1992, the province exempted new construction from rent controls for five years, and in 1998 that exemption was made permanent.

Yet investment in units intended for the rental market continues to be depressed. Instead, I argue that two other concurrent policy changes can better explain this trend. The first was the legalization of condominiums, which shifted the supply and demand incentives in multi-residential buildings and crowded out investment in rental buildings. The second were income and sales tax reforms, which has reduced the profitability of rental buildings.

Of course, there are many other factors and angles we haven’t looked at. We have not controlled for the huge impacts of fluctuating interest rates, demographic trends, land prices, and so on. Tenants are further discriminated by municipal property taxes and exclusionary zoning restrictions. Yet given the timing of these changes, it seems fair to say that rent controls are not the main disincentive operating today.

But if Ontario’s rent controls probably did not impact the supply of new housing, what else can we say about them? How does this evidence fit into the theoretical basis behind most economists’ criticism of rent controls? What evidence do we have from other jurisdictions? What other criticisms are misguided — and which ones are well founded?

A theoretical overview

The many types of controls

The point of this paper isn’t to say that price controls are a paragon of virtue, but instead to critically examine the received wisdom: the picture is rather murkier than that shown in in the standard textbook analysis.

One major problem with this discussion is that there are actually many qualitatively different kinds of rent controls, which different regions have experimented with over different periods of time. When designing a control, we can decide when and how prices increase, whether they track inflation or another indicator, whether capital expenditures can be recovered, at what rate vacant units can reset to what the market will bear (if at all), and so on.49

Richard Arnott, in a widely read paper from 1995, broadly categorizes rent control policy into two distinct phases.50 The first wave, or generation, of controls were enacted around World War II and they imposed nominal rent freezes tied to individual units. In a planned war economy that lacked much in the way of private housing construction, this made a certain amount of sense; but afterwards most regions dismantled their controls and only New York City (and some European cities) maintained that wartime policy.51

The second generation began in the 1970s as rent control ordinances were passed in Boston, Los Angeles, San Francisco and in a variety of towns in California, Massachussetts, New Jersey, New York, etc. The structure of Canadian governance saw these policies accumulate at the provincial level, and during this period ten provinces also enacted rent controls (though most have since abandoned them). These policies “differed significantly from the first-generation rent control programs” and usually allowed automatic increases in rent, the passing through of additional costs, and other like-minded provisions.51

Separating controls into “hard” and “soft” is not especially useful, though. Hans Lind, writing in 2001, defined five distinct functional types of rent control. In his view, regulations can protect sitting tenants from being charged above-market rents (type A), or from increases in rent unattached to increases in costs (type B). Alternatively, regulations can instead bind to units and prevent landlords anywhere from charging above-market rents (type C), prevent rapid inflation by smoothing increases (type D) or, finally, prevent rents from ever reaching actual market prices (type E).52 53

The takeaway here is that when we talk about regulations, we have to be specific since their goals, mechanisms and therefore impacts are going to be different. New York City’s rent controls, which Lind identifies as an extreme version of a type E control,53 are the most famous and well studied example, and consequently critics are quick to conflate all rent regulation with the kind experienced there.54 That tendency is unfortunate, since in doing so they perform a sleight of hand: New York City’s complex and overlapping rent regulations were enacted at different points of time,55 and therefore its experience is idiosyncratic and unlikely to be directly applicable to other cities.

Of course, they’re not wrong to criticize nominal rent freezes. Obviously, a control regime that over time lowers real income below that of real expenditures is a bad idea. It transforms rental properties into endless money pits. It’s fine, and likely necessary, to subsidize some aspects of how we produce or provide housing units in order to achieve our policy goals – but it’s unreasonable to expect that subsidy to be provided to the exclusive detriment of individual landlords. If investors wish to transfer their wealth to tenants they don’t need to go through the trouble of erecting a building.

But that’s a false choice. We’re not limited to choosing between an unfettered market and a ruinously restrictive price control.

In a competitive market, prices don’t increase arbitrarily

When economists discuss losses in efficiency, allocation and welfare, they’re comparing the real world with an idealized “perfectly competitive” market where landlords compete to produce homogeneous housing units, there are no externalities, every actor possesses perfect information, and so on. In this view, a landlord faced with increased demand is free to increase prices and profits accordingly. Abnormally high profits, though, attract other potential landlords who by virtue of adding to the supply of apartments will then drive down their prices.

Given a perfect market, any sketch on a napkin will show that if prices are not allowed to rise with demand then new entrants will stay put, supply will not increase, and shortages will follow. However, given perfect competition, the market prices any landlord can fetch will over the long run equal their marginal cost, i.e. the amortized cost of building and operating a housing unit plus the landlord’s opportunity cost. Put another way, in a well functioning market it’s more or less unreasonable to expect that the rents any given landlord is able to extract will grow much faster than costs and inflation.58

The implication here is that while absolute price ceilings can be and are harmful, there is no obvious reason why price smoothing such that increases match but do not exceed costs should have a strong effect on the incentive to create new rental housing.59 Other economists have reached this conclusion. Writing in 2001, Alastair McFarlane developed an econometric model of rent stabilization and concluded that “because allowing fully flexible base rents permits landlords to capture all of the advantages of a rent growth control, neither the timing nor the density of development will be affected by rent stabilization”, though landlords are incentivized to redevelop sooner than later.60

Trivially, investment in multi-residential buildings is a function of one’s cost of equity, cost of financing and net operating income; developers may invest in a project expecting significant growth in their net operating income, but in a competitive market that is a rather risky assumption. Therefore, even in the absence of rent controls, projects by and large must be cashflow positive given rents available immediately post-construction.62

As far as new supply is concerned, we can therefore conceive of a non-harmful rent control: if prices increase with costs and inflation, landlord cashflows should largely be unaffected. It’s easy to see why: a cost-adjusted tenancy rent control primarily impacts only one area of the development process: the initial lease up of an empty building.63 Given the long-term nature of multi-residential investment, and provided with the ability to adjust for initial mistakes, over the long run the impact on their finances should be reasonable if not minimal – and their business model can be satisfied so long as cashflows keep up with costs and capital expenditures.

Consider GWL Realty Advisors, whose president Paul Finkbeiner was quoted in the Financial Post:

“We believe there is a strong demand for rental apartments and this property will lease up over time,” Finkbeiner said about his Livmore project, […] “Apartments provide good long-term returns and very low vacancy levels, it’s just one of the best assets classes from a stability point of view.”

…

GWL seems to think it can work within the new provincial rules. “As a developer, we are building something that will last for 25-50 years that works for tenants,” said Finkbeiner. “We want long-term renters which is also consistent with our investors that are long-term in nature. These buildings go to pay pensions and people’s investments.”

He noted Ontario still allows rents to be raised to market level once a tenant leaves a unit and capital improvements to buildings can also be passed on to tenants.

“All we want is a fair rent for our apartments, we do not want above guidelines. We have been able to work within rent controls and still deliver a good product for our investors and tenants,”64

Evidence on supply from other jurisdictions

Recall that Ontario’s current rent control regime pegs rents to inflation, does not control rents between tenants, and allows cost pass through. Lind categorized it as a type B control,53 and elsewhere it is variously called a kind of tenancy rent control or rent stabilization.

We saw earlier that though Ontario’s previous rent control regimes may have been harmful, they were unlikely to be the main disincentives acting on supply since 1998, when vacancies were decontrolled and new construction was exempted entirely. Since we need to compare apples-to-apples, what other evidence can we draw for the impacts of type B rent controls?

Consider Manitoba, whose regulation scheme is broadly similar65 and has regulated rents since roughly 1976. Hugh Grant, writing in 2011, argues that there is no evidence that Manitoba’s rent regulation program had a negative effect on the supply of new, or maintenance of existing, rental properties. Manitoba at the time was experiencing a low vacancy rate, which Grant attributed to a rapid influx of immigration, and a relatively inelastic supply due to large planning-to-completion time lags and uncertainty about future rates of population growth.66

In New Jersey, over one hundred municipalities have enacted their own rent controls. Each city implemented their regulation differently, but by and large they all permit automatic increases, passing on capital improvements, etc; almost half also engage in vacancy decontrol. In 2015, Joshua Ambrosius et al used the 2010 United States Census and compared the regulated cities with unregulated cities. They found that, once they controlled for other factors, New Jersey rent control policies had no statistical impact on rental quality, rental supply, property appreciation or foreclosure rates in the cities that enacted them.67

In fact, tenancy rent controls seem to barely control rents at all. Earlier this year, Graham Haines analyzed Ontario’s rent regulations and developed a model that estimated that “the discounted cumulative income earned by the rent controlled building was between 98.5% and 99.0% of that earned by the non-rent controlled building”.68

This finding is corroborated by both the Manitoba and the New Jersey study cited above. In New Jersey, median rents in rent controlled cities were found to be roughly the same as rents in non-controlled cities.69 In Manitoba, Grant argues “there is no evidence that rent regulations have restricted rents below what would prevail in a perfectly-competitive market under equilibrium conditions”.70

Though they do not quite confirm to my criteria above, two other studies are worth mentioning. Frank Denton et al, in a 1993 report commissioned by the CMHC, developed an econometric model and conducted an extensive empirical investigation of the impact of rent controls on Canadian housing markets. They concluded that “there is no evidence that controls influence the long-run rate of increase of rents”, nor did they impact housing starts or maintenance though they may lower vacancy rates.71 72 Celia Lazzarin analyzed rent regulations in British Columbia from 1974 to 1984 for her 1990 master’s thesis. She found that basically there were too many confounding variables (demographics, unemployment, interest and inflation rates, migration, etc) to attribute the declines in Vancouver’s rental supply solely to rent controls.73 74

Controls probably incentivize tenure conversions, though

There is one noticeable disadvantage to a tenancy rent control: in tight markets the delta between long term tenant rates and market rates can grow rather large.

Because rents reset between tenants, landlords therefore may try to select for shorter term tenancies (i.e. by preferring students over families) and building smaller units. Lawrence Smith wrote about this in 2003, as well as Richard Arnott.19 61

Keeping some rents below market prices has another detrimental effect: it encourages property owners to economically evict their tenants via renovations or to convert to unregulated forms of tenure. At the beginning of this paper, I reviewed Lawrence Smith’s 1988 paper which mentions this for Toronto, and earlier I cited McFarlane (2001). I’ve chosen to highlight three other papers.

Writing in 2017, Martine August documented the financialization of multi family residential properties in Toronto. Aided by the deregulation of capital markets, the end of Canadian social housing provision and historically low interest rates, private equity funds and real estate investment trusts have been buying up aging rental properties – with the explicitly stated purpose of turfing their existing low-income populations in order to renovate and gentrify their units.75

David Sims, writing in 2007, examined what happened after Massachusetts ended rent controls in 1994. He argues that units in previously controlled areas became 6 to 7 percentage points more likely to be rented out (i.e. that units were kept from the rental market).76 77

Rebecca Diamond et al, in a paper published in 2017, leveraged a uniquely rich dataset. In 1994, the city of San Francisco extended its rent regulation to buildings with 4 or fewer rental units built before 1980 (about 30% of the rental stock). Combining a private data provider with property records, they were able to follow individual San Francisco tenants occupying regulated and unregulated housing units from 1994 to the present day. They found “that rent-controlled buildings were almost 10 percent more likely to convert to a condominium or a Tenancy in Common”.78

There is some reason to doubt these numbers prima facie, since converted housing units remain part of the housing stock – and a large percentage of condominiums are rented out to tenants without this necessarily being reflected in most housing data sources (though it seems that Diamond’s dataset mostly controls for this). It may be more accurate to say that primary rental units are being converted to ownership and the secondary rental market.

In addition, California’s Ellis Act creates a relatively permissive environment for conversions. This is in contrast with Massachusetts, where Sims found that “rent decontrol is associated with an 8 percentage point increase in the probability of a unit being a condominium”, presumably since conversion restrictions were lifted alongside controls.77 Nevertheless, it seems fair to conclude that keeping units below market rates exacerbates the incentive towards selling them or redeveloping them.

I think it is important to distinguish between conversion to ownership tenure and “renovictions”. Reading these papers I can’t help but think that the actual problem with condominium conversions has more to do with rising land values and the lack of new supply. That regular, continuous growth in market rates makes conversions attractive is not surprising. San Francisco’s property values have appreciated by 550% over the last thirty years,79 and it rather famously doesn’t build much in the way of new housing despite creating lots of well paid jobs.80 As seen in Massachusetts, condominium conversions can likely be regulated or disincentivized.

With regard to “renovictions”, I think we can ameliorate these conditions by moderately controlling vacancies, paired with a temporary exemption for new construction. If inter-tenancy rent increases are restricted by 10% or even 5% over inflation we reduce the incentive for high tenancy turnover and smooth rapid price increases across the market,81 while preserving the normal incentive structures and business models previously described.

Affordability is about the land

The essential observation here is that rent controls cause a decline in rentals not because they are rendered unprofitable or unsustainable, but because they are crowded out by ownership housing and other, more profitable uses. Today’s land prices set the floor on the rent tomorrow’s new supply needs to extract, and so it seems that when we talk about letting rent prices float to market rates, we imply that landlords deserve to capture the growth in value immediately rather than just through capital gains.

To the extent that increases in land values in certain cities are a function of inelastic supply, capital markets and low interest rates, that seems like a strange reason to support a transfer from tenants to landlords. In fact, allowing landlords to arbitrarily increase prices and extract value gains immediately likely incentivizes existing investors to prefer a regime of supply inelasticity – since no new investment or activity is necessary from their behalf to reap the benefits.

Ultimately, our housing crisis is a matter of income: tenants with low incomes have an income problem, not a housing problem.82 83 Land prices and other costs, driven by restrictive land use policies and the speculative bubble, have grown faster than tenant incomes and pushed financial recovery rents beyond what most of the rental population can afford or finds reasonable. While land prices continue to grow above inflation or wages, maintaining affordable housing stock will continue to be a challenge.

In the absence of subsidies, the private sector is unlikely to build new rental housing for the low end of the market. Though the profitability of building modest cost ownership housing in large volumes can approach that of smaller quantities of high-end ownership housing, the same is not true for affordable rentals. It costs only slightly less to build an affordable rental, compared to building high end, but the resulting income stream is substantially smaller.33

Relatively affordable privately developed housing, then, occurs because as inflation and mortgage payments decrease carrying costs over time, the rent necessary to carry a rental investment decreases. And, through a process called filtering, new high-end housing creates vacancies lower in the chain as people move on up to occupy new supply. In theory, as the existing housing stock ages and deteriorates, people with higher incomes will tend to prefer newer, higher quality housing.84 In practice, as housing preferences change and formerly ‘downtrodden’ areas become trendy, the filtering chain can get interrupted as higher-income people renovate and move into formerly lower-income areas.

In review

Commentators criticizing rent controls often point to New York City as a negative example, but that city’s experience is rather idiosyncratic. The design and implementation of rent controls varies so much that we must be careful and specific when making comparing different regions.

Price controls are bad in so far that they render the production of goods and services untenable: absent subsidies, a landlord must be able to recoup her investment from the rent she extracts from her tenants. Conversely, as long as landlords can recover increases in their costs over time, their business models should be unaffected. While first generation controls were likely to be as harmful as described, there is no theoretical reason why a well-designed rent control should disincentivize new construction. This outcome is confirmed by several theoretical and empirical studies.

However, a well-designed rent control allows landlords to pass through capital expenditures and somewhat incentivizes renovations, and therefore does not directly help with gentrification. A well-designed rent control does not disincentivize new supply but it doesn’t ease supply inelasticity either – and therefore by itself cannot ensure affordability.

What are rent controls good for, then? That a regulation is relatively neutral does not justify its implementation.

The role of security of tenure

Rent control and the prevention of precarity

The economics literature on rent controls has much to say about efficient allocation, property values, maintenance and the supply and demand for rental housing, but unfortunately economists and other commentators rarely seem to have anything to say about security of tenure.85

The omission is glaring. In a 2003 paper reviewing tenancy rent controls, Richard Arnott noted that:

Almost all economists lead financially secure lives and were raised by parents who emphasized responsibility and self-discipline. They have little or no personal experience with the insecurity that is ever-present in the lives of the less advantaged—those from dysfunctional families, those not raised to middle-class values, and the less able—who tend to live from one paycheck to the next. Not surprisingly, therefore, most economists ignore or underemphasise the importance of security of tenure in rental housing, even though it is consistently second only to affordability on the list of concerns raised by tenant groups.87

Security of tenure is the idea that you have the right to occupy your home and be protected from being forced to leave against your will. By way of contrast, a homeowner’s right to security of tenure is usually taken for granted. So long as they’re current on mortgage payments (if any), taxes, etc, a homeowner is protected from involuntary eviction. That security is not absolute, of course: they may be expropriated or rising interest rates may render them unable to afford their home, but by and large “they cannot be forced out at the whim of someone else”.88

By default, in most common law jurisdictions tenants do not have this security. They may be denied a renewal of their lease, they may be subject to seizure by landlords who simply dislike them, or they may be ‘economically evicted’ due to arbitrary increases in their rent. Providing tenants with security of tenure (i.e. protection from involuntary or arbitrary eviction) requires that we not only ensure that housing units are well-maintained and safe for inhabitation, but that we also prevent landlords from unduly exercising their economic power over tenants.

Earlier, I examined the theoretical basis for a well-designed rent control, and concluded that it was an ineffective tool for ensuring affordability or preventing gentrification. However, rent regulations do seem to be effective at keeping current tenants in their homes.

For example, consider the case of Massachusetts, which abolished its rent controls in 1994. Four years later, the Economist reported that in Cambridge “nearly 40% of tenants in regulated flats moved out after rent control ended”, and that “decontrolled rents overall jumped by more than 50% between 1994 and 1997”.89 David Sims, writing in 2007 about the same decontrol event, found that “decontrol is associated with a decrease of renter stays of 1.84 years”, which is rather “sizeable when compared to the mean renter stay of 6 years in the sample”.77 This is framed as a loss of efficiency in terms of labour mobility, but I’m not sure it’s that cut and dry.

Most striking is the result from Rebecca Diamond et al’s research. They frame rent regulations as a kind of insurance against rent increases whose cost in practice is borne by all tenants, as the restriction in supply causes unregulated or vacant rents to rise more than they would have otherwise. They then found that tenants receiving rent control were up to 20% likelier to remain in their apartments and that “absent rent control essentially all of those incentivized to stay in their apartments would have otherwise moved out of San Francisco”. Diamond et al conclude that the gains in welfare those tenants experience narrowly outweigh the resulting deadweight loss incurred on others, but argue that providing this insurance function directly as a government subsidy or tax credit would be more efficient.90 78

Given that the welfare gains for San Francisco alone are measured in the billions of dollars, that could be a sizeable intervention. But why shouldn’t we intervene? After all, we substantially subsidize private ownership. Its relative attractiveness as an investment is the direct result of government policy. The relative scarcity of land via exclusionary zoning is a government policy. Financial liberalization and the coupling of capital markets to home financing was the result of government policy.

Most suggestions for how to improve the affordability of rental buildings involve either direct subsidies or the reinstitution of tax shelters, and the extent to which they are built at all today in Canada would not happen without the direct intervention of a government agency, the CMHC. It’s not like our housing markets exist in a state of nature.

A brief history of housing in Canada

Property rights and the markets they enable exist to the extent they are enforced and protected by the state. When we establish and regulate rights, we typically seek to balance the interests and concerns of everyone involved, and revisit those tradeoffs as our values and goals shift over time. We think our food should be safe to eat, our doctors should be well trained, and that you shouldn’t dump waste anywhere you feel like.

In Canada, it would be difficult to identify a time when we had a completely laissez-faire housing market. Some of our earliest municipal by-laws regulated building standards. First, we sought to improve our health, safety, fire, and construction standards, and later we gradually began to add a host of land use and development regulations.91

These regulations led to the elimination of unhealthy, unsafe and poor quality housing in urban areas. If in 1951 almost one out of every ten houses lacked basic plumbing facilities, by 1982 that had dropped to 1.6%.92 However, our improved housing standards and growing restrictions on land use led to an increase in the cost of its manufacture. As early as 1914, it became apparent that the private market alone was not providing enough low income housing.91

One intervention begat another. Federal incentives were introduced in 1938 to stimulate the development of low income rental housing, and by 1949 the government began to invest directly in its production.91 Buoyed by the post-war economic and population boom, we began to seriously expand our welfare state and, concerned with ensuring “enough rental housing production to nourish the golden goose of urban growth”, from 1965 to 1995 up to 10% of all new housing was some mix of social housing.93

These interventions were not limited to the poor – quite the opposite. In 1946, the CMHC was established with the aim of increasing home ownership among the broad middle and lower-middle class. Focusing mainly on making amortized mortgages work for house buyers and private investors in rental housing, by the mid-1960s most households obtained at least part of their mortgage loan directly from the federal government.94

In fact, most of the history of the role of Canadian government housing policy is an effort to assist ownership. In 2005 alone, more individual homeowners were helped through mortgage insurance than the number of all social housing units funded since the 1970s. In addition to creating cheaper loans, the federal government also provides subsidies through a variety of tax credits, tax sheltered investment vehicles, and tax exemptions. When the federal government began taxing capital gains it exempted the sale of primary residences, which by 2008 was costing almost $6 billion a year in uncollected revenue.94

In so far that our housing policy has targeted the middle class’ standard of living, it has been rather successful. As an investment asset, home ownership confers unique benefits: it provides shelter as well as equity that can be withdrawn later in life. Canadians who pay off their mortgages spend on average only 11% of their income on housing and, by 1999, the average homeowner earned 208% more income, and owned 70 times more wealth, than the average tenant.94

Tenants have rights too

This is to say, “what kind of living conditions do we want people to enjoy?”, and consequently, “what, exactly, should be the goal of our housing system?” have been considered important questions for over a century. Our answers to these questions have shifted over time. We began by regulating the safety of our housing, and today we significantly subsidize its ownership for those who can afford it.

Similarly, our perception of the nature of the relationship between property owners and tenants has also shifted.95 Under common law, which concerned itself with a leaseholder’s (agricultural) relationship to the land, a landlord was under no statutory requirement to maintain the premises or conduct any repairs. Nor were there any limits on their power to evict or even seize the property of tenants. A review of the applicable laws in 1968 found that landlords possessed such a disparity of bargaining power that tenants did not have a freedom of contract in any real sense.96

For a variety of ethical, legal and economic reasons, it became clear that tenants deserved protection, and that applying antiquated land law principles to the modern urban apartment was totally unsuitable. Gradually the law caught up: Ontario adopted its first residential protection laws in 1970, while the notion that tenants deserve security of tenure was added by 1975. Today, landlords are seen as responsible for providing safe and livable accommodations, and that tenants should be protected from arbitrary evictions.88

Often, this is framed as a conflict of self-interests between landlords and tenants, where tenants suffer disproportionate costs when forced to move, and benefit from stability. In a perfect market, the average tenant should be free from arbitrary increases or poorly maintained units due to the emancipating effect of competition. But in practice, that doesn’t seem to describe reality. Given the possibility of economic eviction, the regulation of security of tenure must be accompanied by the regulation of rent.98 David Hulchanski, writing over thirty years ago, compares rent regulations to consumer protection laws:

Where the rental market cannot function normally, such as in meeting supply, or when moving costs limit the mobility of consumer rental services […] regulations protect consumers who find themselves in inferior bargaining positions.98

Every regulation imposes tradeoffs, and in that light we can compare the regulation of rent with the regulation of fire safety. Mandating that landlords’ properties satisfy certain minimum fire safety standards also raises costs and therefore diminishes the affordability of housing. Though some are happy to make that macabre argument,99 by and large we’ve decided it’s a cost worth bearing: individual people are rarely in position to demand improved construction standards, and fires impose costs on everyone around it. At some point, we will always be dealing with thresholds and equilibriums, and it is up to society to decide what is or isn’t acceptable: in Ontario, only about 7 people per million die every year in residential fires.100

And, much like fire safety, security of tenure doesn’t just benefit individual tenants. The stability provided by security of tenure is the stuff from which well functioning communities are made of.

Security of tenure is a public good

In economics there exists a concept of a “public good”, which broadly applies to any “service” or “thing that people derive benefit from” that is both non-excludable and non-rivalrous. Non-excludable means that you can’t prevent people from enjoying it; non-rivalrous means that by enjoying the good you are not depriving other people from doing the same.102

The classical examples include clean air, national security, knowledge, and so on. I can’t prevent you from breathing in the same fresh air that I’m enjoying, and when you consume official government statistics you are not depriving me of the same benefit. Public goods aren’t necessarily provided by the state, much the same way that the state provides access to some private goods. The distinction is relevant because the nature of public goods incentivizes people to be jerks and therefore public goods “must be provided for everyone if they are to be provided for anyone, and they must be paid for collectively or they cannot be had at all”.103

Though housing itself is a private good, one’s enjoyment of security does not impinge on the security of others. As we’ve seen, security of tenure cannot be provided without a collective investment of some sort since individual tenants rarely possess the bargaining power to afford it themselves. But more importantly, security of tenure provides benefits to the community at large – and also suffers from the free-rider problem that plagues other public goods.

Security of tenure is good for the public

Our communities consist of both physical infrastructure, like roads and public transit, as well as “human” infrastructure, like community organizations and loose neighbourhood ties. A neighbourhood may be desirable for its proximity to a grocery store – but also for the quality of its schools, the absence of crime and the vitality of its community events. A healthy neighbourhood is one where its residents are looking out for one another.

When landlords raise rents above costs, they are in effect cashing in on new or improved local amenities provided either by the state or the local community itself. The reduction of crime, or the expansion of public transit, readily provide rationales for increasing rents. Creating conditions where tenants may reasonably fear investment in their communities is a rather perverse outcome.

Tenants face substantial hurdles. I recently read Matthew Desmond’s incredible and harrowing book Evicted, in which he followed several low-income renters in the city of Milwaukee over the course of a year. Early on, he writes:

“The public peace–the sidewalk and street peace–of cities is not kept primarily by the police, necessary as police are. It is kept primarily by an intricate, almost unconscious, network of voluntary controls and standards among the people themselves, and enforced by the people themselves.” So wrote Jane Jacobs in The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Jacobs believed that a prerequisite for this type of healthy and engaged community was the presence of people who were simply present, who looked after the neighborhood. She has been proved right: disadvantaged neighborhoods with higher levels of “collective efficacy”–the stuff of loosely linked neighbors who trust one another and share expectations about how to make their community better–have lower crime rates.

Towards the end of the book, he adds:

Residential stability begets a kind of psychological stability, which allows people to invest in their home and social relationships. It begets school stability, which increases the chances that children will excel and graduate. And it begets community stability, which encourages neighbours to form strong bonds and take care of their block. But poor families enjoy little of that because they are evicted at such high rates.

…

Eviction even affects the communities that displaced families leave behind. Neighbors who cooperate with and trust one another can make their streets safer and more prosperous. But that takes time. Efforts to establish local cohesion and community investment are thwarted in neighborhoods with high turnover rates. In this way, eviction can unravel the fabric of a community, helping to ensure that neighbors remain strangers and that their collective capacity to combat crime and promote civic engagement remains untapped.104

Faced with the unpredictable but certain need to move in the near future, it’s harder to establish deep ties to a neighbourhood. As a result, tenants are routinely discounted or ignored by our political structures,105 and face greater hardships accessing necessary social services and economic opportunities.

In 2016, the New Zealand Housing Foundation commissioned Charles Waldegrave et al to undergo a literature review of the “Social and Economic Impacts of Housing Tenure” and the results are rather bleak. Being a homeowner, as opposed to a tenant, means you live longer and are both physically and psychologically healthier. It makes you less likely to retire early due to health reasons and homeowners on average spend less time unemployed. Owners live in neighbourhoods with lower crime rates, and their children are less likely to suffer from depression, and are more likely to graduate from high school.107

Some of these effects are undoubtedly due to homeowners’ higher levels of income and wealth. Life is much less stressful if you have the financial cushion to weather various misfortunes. However, these effects mostly persist even after controlling for socio-economic status and/or income. Waldegrave et al note that their study is limited, and did not include studies that focused on mortgage and rent stress though “it is acknowledged that unaffordable housing of whatever tenure type will almost certainly lead to negative health and social outcomes”.107 A few of the studies they encountered did not find meaningful differences once they accounted for residential stability – and, after income, that instability is arguably the main source of stress differentiating owners from tenants.

In practical terms, it’s hard to avoid the inference that being a tenant is a rather harsh externality that our housing policies impose largely on the poor and the recent immigrant.

Conclusions

A popular urbanist school of thought posits that our cities are the economic engines of the future. Globalization diminished the importance of physical distance in the manufacturing economy, but the resulting shift to the service economy has magnified the importance of clustering effects and economies of scale provided by greater densities of goods and people – to say nothing about the looming threat of climate change and the environmental unsustainability of our low density suburbs.

In this view, it’s not hard to imagine a near future where the equity requirements of residential ownership (let alone freehold structures) has priced out most people. Back in March 2017, CIBC’s Benjamin Tal wrote that “the GTA market is fast approaching a full-blown affordability crisis” as a surge in demand due to “a notable increase in speculative and flipping activity” is pricing out most people from ownership markets. He argues that therefore municipalities must “rethink the role of rental activity in the region’s housing mix”.108 Though I am prone to quibble with some of his preferred solutions,109 it seems correct to observe that current macro economic conditions are rushing us towards a new era of unobtainable ownership prices.

In 2011, a little under half of the population of the city of Toronto rented their housing,110 and the preliminary results from the 2016 census suggest renting is poised for a comeback. Rental housing dominates recent growth and change, and home-ownership is now out of reach for the young and the middle- and low-income.111 It’s become fun for real estate commentators to shrug and joke about life being unfair,112 but our housing universe and its financing mechanisms aren’t just some random happenstance – they’re the result of decisions and policies we have made over the decades.

Critics do us a disservice by pretending rent controls are about affordability or supply. The best rationale for instituting rent controls is that of ensuring security of tenure, and in an environment where rents are rapidly increasing it becomes necessary to regulate rent. Not only do tenants deserve security of tenure, but they lead healthier, more productive lives in safer, more pleasant communities when residential stability can be taken for granted. Early rent controls were poorly designed; but a regulation that controls the rate of price inflation, while allowing for legitimate cost increases to be recouped, can be both sustainable and equitable.

A close examination of recent construction starts, and policy changes affecting the economics of purpose built rental buildings, reveals that Ontario’s rent regulations are likely not the main disincentive removing supply from our housing markets. The legalization of condominiums in 1967 and the federal government’s overhaul of the Income Tax Act in 1972 (amongst other tax changes) had a big impact on the relative profitability of rental buildings, and are likely the cause of their decline relative to other kinds of housing.

Almost no two rent controls are the same, and one has to be very careful when comparing different cities or regions. There is evidence from other jurisdictions with similar kinds of rent controls to that of Ontario’s current regime that shows a lack of effect on the supply of new housing. Anyone who, when discussing rent controls, does not bring up the problem of security of tenure, or blithely compares regulations from different jurisdictions, may be pulling your leg.

Finally, housing is complicated and our governments routinely intervene and shape its outcomes. They did a great job creating and subsidizing suburbs and middle class ownership, but they are currently failing the poor and people who live in cities.

For better or for worse, renting is the future. Long-term tenants have a legitimate interest in staying in the communities they have made successful – and it’s in society’s interest that they lead stable, successful lives. Tenants do not deserve to be subjected to a tenure regime that significantly disadvantages them socially, economically, and politically compared to the subsidized homeowning population.

Tables

- Ontario Housing Starts 1969-2016

- Toronto Housing Completions 1981-2016

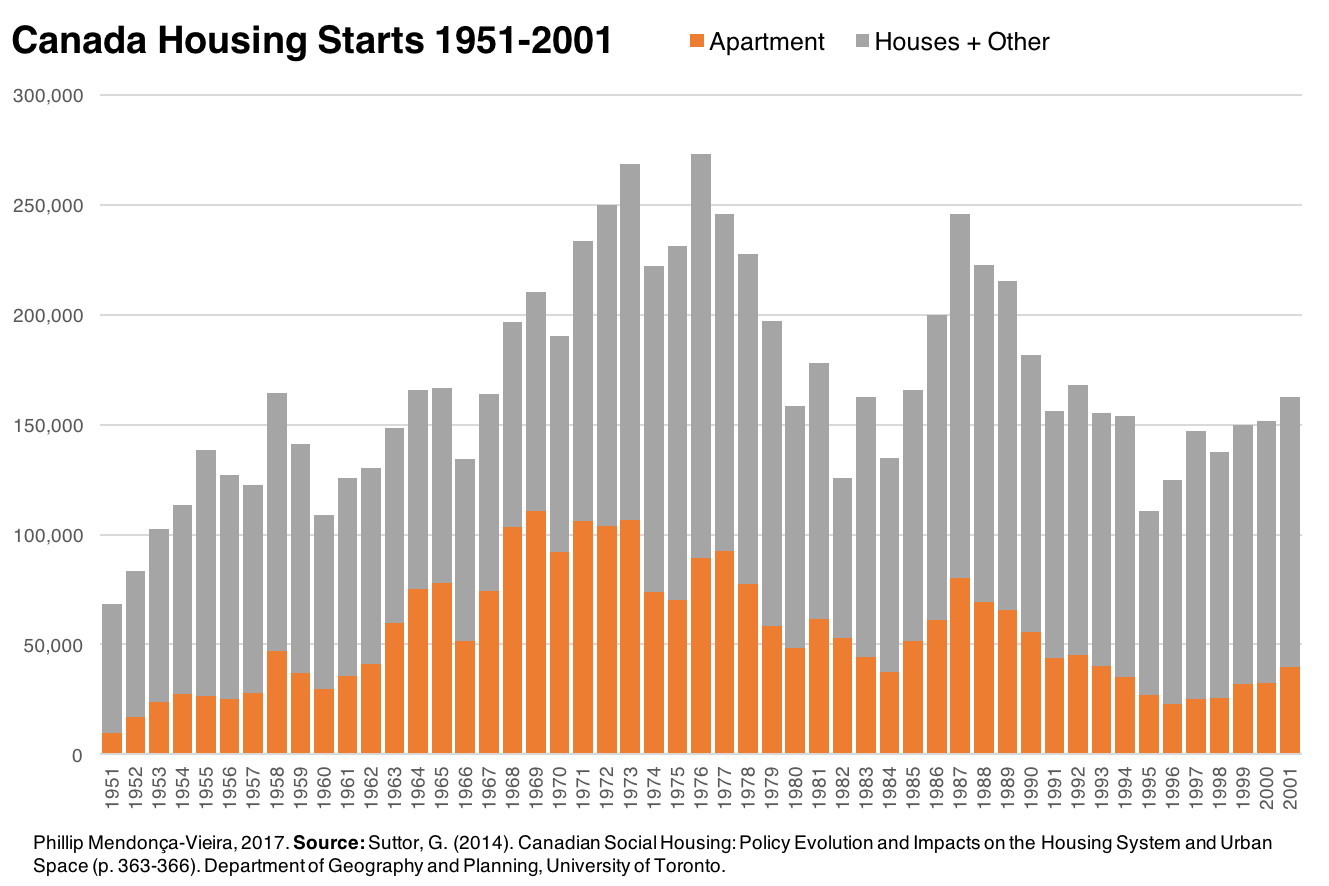

- Canada Housing Starts 1951-2001

References and footnotes

-

Landlord and Tenant Board. (2017, May). Brochure: A Guide to the Residential Tenancies Act. Retrieved September 29, 2017, from sjto.gov.on.ca ↩

-

McGrath, J. (2017, March 22). Ontario needs a rental rethink, but should tread carefully. Retrieved August 17, 2017, from tvo.org ↩

-

McFarland, J. (2017, April 4) ‘Exact opposite of what is needed’: CIBC slams Ont. rent-control rules. Retrieved August 17, 2017, from theglobeandmail.com ↩

-

Gee, M. (2017, April 20). Rent control isn’t the solution to Ontario’s housing problem. Retrieved September 12, 2017, from theglobeandmail.com ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Tal, B. (2017, April 4). Rent Control—The Wrong Medicine. Retrieved September 12, 2017, from economics.cibccm.com ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Selley, C. (2017, March 21). Chris Selley: Rent control is a bad solution to the wrong problem. Retrieved September 12, 2017, from nationalpost.com ↩

-

Lafleur, S., & Filipowicz, J. (2017, April 15). Rent controls wrong answer to housing crisis. Retrieved September 12, 2017, from torontosun.com ↩

-

McGillivray, K. (2017, April 05). Ontario second-worst economy for young people in Canada: report. Retrieved September 12, 2017, from cbc.ca ↩

-

Martin, S. (2017, February 22). No fixed address: How I became a 32-year-old couch surfer. Retrieved September 29, 2017, from cbc.ca ↩

-

Jaafari, J. D. (2017, April 14). Toronto tenants crushed by rent hike exemptions. Retrieved September 29, 2017, from theglobeanmail.com ↩

-

Mercer, G. (2017, May 13). Tenants sound alarm on creeping rents. Retrieved October 31, 2017, from therecord.com ↩

-

City of Toronto (2006) Rental Housing Supply and Demand Indicators. Toronto City Planning and Policy Research ↩ ↩2

-

Not only does it make a frequent appearance in the literature, both the Globe‘s Marcus Gee4 and CIBC’s Benjamin Tal5 cited it when writing their rent control skeptic op-eds in 2017. ↩

-

Smith, L. B. (1983). The Crisis in Rental Housing: A Canadian Perspective. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 465(1), p. 3-4, 58-75. doi:10.1177/0002716283465001006 ↩

-

Smith, L. B. (1988). An economic assessment of rent controls: The Ontario experience. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 1(3), 217-231. doi:10.1007/bf00658918A ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Miron, J. R. (1995). Private Rental Housing: The Canadian Experience. Urban Studies, 32(3), 579-604. doi:10.1080/00420989550012988 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

In the absence of ‘vacancy control’, rents are allowed to reset to market rates when tenants vacate their dwellings, i.e. the control binds to the tenant and not the dwelling unit. ↩

-

Staff report for information on Tenant Issues Related to the RTA 1 (Rep. pg 2-3). (2013, October 15). Retrieved August 28, 2017, from toronto.ca ↩

-

Smith, L. B. (2003). Intertenancy Rent Decontrol in Ontario. Canadian Public Policy / Analyse de Politiques, 29(2), 213. doi:10.2307/3552456 ↩ ↩2

-

Tenant laws were changed again in 2006, but rent controls were unaffected. ↩

-

Brescia, V. (2005). The Affordability of Housing in Ontario: Trends, Causes, Solutions (p. 31). ↩

-

As people age through their lifecycles they occupy different kinds of housing. As we will see later in this paper, Canadian policy is heavily weighted towards homeownership and so the relationship between vacancy rates in Toronto and the corresponding age pyramid in Ontario is rather obvious. Vacancy rates climbed in the 1990s as boomers entered the ownership market, and dipped again in the late 2000s as millennials, the next disproportionately large cohort, became of age.24 ↩

-

Hans Lind, writing in 2003, noted both that the “[Smith (1988)] study is very crude, as there is no control for other factors.” (p. 149) and that useful housing economic models are hard to develop given the required volume of empirical data (p. 151)25 ↩

-

Government of Canada (2017, May 01). Historical Age Pyramid. Retrieved October 20, 2017, from statcan.gc.ca ↩

-

Lind, H. (2003). Rent regulation and new construction: With a focus on Sweden 1995-2001. Swedish Economic Policy Review, (10), 135-167. ↩

-

The CMHC’s website only provides convenient access to data back to 1990. For information prior to then, I had to look it up in individual yearly housing statistics publications. However, the yearly publications only began to distinguish starts or completions by intended market starting in 1985 (presumably this data was collected prior to then, but simply not aggregated and published). In order to make the time frame being compared as similar as possible, I relied on a City of Toronto report. ↩

-

Hanes, T. (2008, February 23). Happy 40th. Retrieved September 18, 2017, from thestar.com ↩

-

Black, J. (September 2012). The Financing and Economics of Affordable Housing: Development Incentives and Disincentives to Private-Sector Participation (p. 8-9, 20), Cities Centre, University of Toronto ↩

-

Pomeroy, S. (2001, October). Toward a Comprehensive Affordable Housing Strategy for Canada (p. 15). ↩

-

Discussing housing construction in Stockholm, Hans Lind (2003, p. 159) wrote: “Very few new projects were also started in the suburbs around the year 2000, as production costs had increased faster than the willingness to pay. This can be seen as a kind of Dutch disease, where the increase in factor prices generated by some profitable sectors—the centrally located condominiums—makes other “low-margin” sectors unprofitable.” ↩

-

Rental buildings are GST/HST exempt, as opposed to zero-rated – meaning that unlike other businesses they can’t pass on sales tax to final consumers.35 ↩

-

Housing Supply Working Group. (2001, May) Affordable Rental Housing Supply: The Dynamics of the Market and Recommendations for Encouraging New Supply, p. 9-14, 17-18 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Federation of Rental-housing Providers of Ontario (2015) Removing Barriers to New Rental Housing in Ontario (p. 18) ↩

-

Lampert, G. (2016). Encouraging Construction and Retention of Purpose-Built Rental Housing in Canada: Analysis of Federal Tax Policy Options (p. 6). ↩ ↩2

-

Crook, T. (1998) The Supply of Private Rented Housing in Canada. Netherlands Journal of of Housing and the Built Environment, 13(3), 339 ↩

-

Benson, E. J. (1971, June 18) Budget speech delivered by the Honourable E. J. Benson Minister of Finance and Member of Parliament for Kingston and The Islands. Retrieved from budget.gc ↩

-

It’s easy to understate these reforms because the true scope of the changes is a hard story to tell. There are a good half dozen different tax levers being pulled at different times: depreciation rates were altered, deductions eliminated, investment rules were changed and so on in 1972, 1974, 1978, 1981, 1986, etc. To compensate for these changes, the federal government introduced a variety of subsidies, like the Multiple Unit Residential Building in 1974, the Assisted Rental Program in 1975, etc, etc. If you want to go deep on these topics, see Clayton (1998), Housing Supply Working Group (2001), and Miron (1995), among many others cited in this article. ↩

-

Clayton, F. (1998, November) Economic Impact of Federal Tax Legislation on the Rental Housing Market in Canada (p. i, 9-12) Canadian Federation of Apartment Associations - Fédération Canadienne des Associations de Propriétaires Immobiliers ↩ ↩2

-

Enemark, T. (2017, July 06). Fastest Way to More Rental Housing? Tax Changes. Retrieved September 12, 2017, from thetyee.ca ↩

-

Clayton (1998, p. 9, 32-33) ↩

-

Steele, M. (1993) Conversions, Condominiums and Capital Gains: The Transformation of the Ontario Rental Housing Market. Urban Studies 30(1), 103-126 ↩ ↩2

-

Crook (1998, p. 335-336) ↩

-

Goldberg, M. A., & Mark, J. H. (1985). The Roles of Government in Housing Policy A Canadian Perspective and Overview. Journal of the American Planning Association, 51(1), 35-36. doi:10.1080/01944368508976798 ↩

-

Suttor, G. (2009). Rental Paths from Postwar to Present: Canada Compared (p. 39-40, Research Paper 218). Toronto: Cities Centre University of Toronto. ↩

-

Clayton (1998, p. 14, 28) ↩

-

Ah ha, you say, but rent controls are illegal in Washington State. Yet condominiums don’t get built because of prohibitive building standards. It’s complicated and hard to compare! ↩

-

Morales, M. (2017, August 14). Why Seattle Builds Apartments, but Vancouver, BC, Builds Condos. Retrieved September 13, 2017, from sightline.org ↩

-

For a more exhaustive treatment of the literature, see Lind (2001) and (2003), Brescia (2005), Jenkins (2009), Grant (2011) and Ambrosius et al (2015)} ↩

-

This distinction between “first” and “second” generation or “hard” and “soft” controls is not original to Arnott; Hulchanski (1984) also refers to them that way and it’s likely that categorization was made contemporaneously when these controls were enacted in the 1970s. ↩

-

Arnott, R. (1995). Time for Revisionism on Rent Control? Journal of Economic Perspectives,9(1), 100-102, 112-115. doi:10.1257/jep.9.1.99 ↩ ↩2

-

I am not sure that Lind’s categories are especially useful for comparing different regulatory systems, in so far that its abstraction elides too many relevant details. However, it’s great for illustrating the wide variety in intent and implementation. ↩

-

Lind, H. (2001). Rent Regulation: a Conceptual and Comparative Analysis. European Journal of Housing Policy, 1(1), 41-57. doi:10.1080/14616710110036436 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

For example, both the Globe‘s Marcus Gee4 and CIBC’s Benjamin Tal5 cite New York City when writing their op-eds. ↩

-

NYC distinguishes between rent controls, which target buildings built before 1947 and continuous tenancy prior to 1971, and rent stabilization, which targets buildings built prior to 1974 with rents under $2,700. Different tenants under different systems have different rights. Rent controls may have been a nominal freeze when they were enacted, but today landlords are entitled to a 7.5% increase per annum.56 57 ↩

-

New York City Rent Guidelines Board. (2016, September 23). Rent Control FAQ. Retrieved October 30, 2017, from housingnyc.com ↩

-

Nonko, E. (2017, August 28). Rent control vs. rent stabilization in NYC, explained. Retrieved October 30, 2017, from ny.curbed.com ↩

-

Arnott makes the case that housing markets are actually monopolistically competitive since housing structures and preferences are not homogenous, there are substantial asymmetries in information, and transactions costs are non-trivial. Consequently, rents are set higher than their efficient level and the corresponding deadweight loss can be mitigated (Arnott 2003, p. 106). But for our purposes we don’t need to engage with this argument. ↩

-

“The introduction of tenancy rent control has no obviously strong effect on the incentives to undertake rental housing construction.”61 ↩

-

Mcfarlane, A. (2001). Rent Stabilization and the Long-Run Supply of Housing. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.283336 ↩

-

Arnott, R (2003). Tenancy Rent Control. Swedish Economic Policy Review, (10), 98 ↩ ↩2

-

Black, J. (September 2012). The Financing and Economics of Affordable Housing: Development Incentives and Disincentives to Private-Sector Participation (p. 8-12), Cities Centre, University of Toronto ↩

-

Tait, S. (2017, April 30). Ontario’s Fair Housing Plan & Purpose-Built Rental Development. Retrieved September 14, 2017, from linkedin.com ↩

-

Marr, G. (2017, July 18). Rent controls, no worries. Developer unveils major apartment complex in downtown Toronto. Retrieved September 14, 2017, from business.financialpost.com ↩

-

Manitoba does not allow the rent in buildings with more than 3 units to be reset on vacancy, but it exempts new buildings for 20 years and has a more generous cost pass through provision. Grant (2011)} ↩

-

Grant, H. (2011, January 31). An Analysis of Manitoba’s Rent Regulation Program and the Impact on the Rental Housing Market. Manitoba Family Services and Consumer Affairs ↩

-

Ambrosius, J. D., Gilderbloom, J. I., Steele, W. J., Meares, W. L., & Keating, D. (2015). Forty years of rent control: Reexamining New Jersey’s moderate local policies after the great recession. Cities: The International Journal of Urban Policy and Planning, 49, 121-133. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2015.08.001 ↩

-

Haines, G. (2017, April 28). Making Cents of Ontario’s Rent Regulation: Assessing the Financial Impact of Rent Control and Developer Incentives. Ryerson City Building Institute. ↩

-

Ambrosius et al (2016, p. 129-130) ↩

-

Grant (2011, p. 24) ↩

-

It’s worth noting that this study suffers from the same problems all econometric studies do: the lack of suitable data, the difficulty of adequately modelling housing markets, etc, and the report itself includes many attached comments to that effect. ↩

-

Denton, F. T., Feaver, C. H., Muller R. A., Robb, A. L., Spencer, B. G. (1993). Testing Hypotheses About Rent Control: Final Report. Ottawa: CMHC. ↩

-

BC’s controls at the time were rather haphazardly designed (increases were set to 8% or 10%, though inflation occasionally exceeded that) hence why I mention it in passing. ↩

-

Lazzarin, C. C. (1990). Rent Control and Rent Decontrol in British Columbia: A Case Study of the Vancouver Rental Market, 1974 to 1989. University of British Columbia. ↩

-

August, M., Walks, A. (2017) Gentrification, suburban decline, and the financialization of multi-family rental housing: The case of Toronto. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.04.011 ↩ ↩2

-

“My results suggest rent control had little effect on the construction of new housing but did encourage owners to shift units away from rental status and reduced rents substantially.” Sims (2007) ↩

-

Sims, D. P. (2007). Out of control: What can we learn from the end of Massachusetts rent control? Journal of Urban Economics, 61(1), 129-151. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2006.06.004 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-