The Roles We Play

February 8, 2026 | #anthropology #kids #history #queer #thinking

I had not felt any change, but to the people around me it was as if I had been profoundly transformed. Strangers held the door open. Old people stopped to chat. Women smiled at me, a new and novel experience.

I had transitioned, and rather suddenly at that. I was still getting used to it. One moment I was yet another tall, scruffy, bearded man – and in the next I had become a new-dad. Moving through the world with a sleeping baby strapped to my chest, I realized I was no longer being seen as a potential threat.

I was harmless now, benign even.

My role in society had changed. Before, I was cannon fodder. Privileged, taken seriously, of course, but also… kind of disposable? Young-ish men, prone to violence and goofy stunts, are meant to wander, to boldly explore – and should the ship start to sink be last in line for the lifeboats.

Now, I was a family man, a father. Fathers are expected to be stoic, strong, islands of stability. They’re meant to be providers, and for this reason they’re also given some slack. Your life gains meaning when you have a kid. Before a judge, you can beg for mercy: please be lenient, your honour, I have a wife and child to support!

In truth, no man can ever be an island: every man is a piece of society, and we all have a part to play in it. Living has always been a team sport. After I had a kid, I found myself thinking about how, as we change, as we move through our lifecycle, we move through different roles.

The expectations society places on us shifts, and our roles shift with them. Maiden, mother, crone is a classic archetype. At different points in your life you may be called upon to be a helpful son, a fun uncle, or a friendly grandfather. The roles to be filled are dictated by these societal expectations – by our culture, by our bodies, and by how we make or obtain the resources we need. Someone has to raise the children, and someone has to hunt for food.

These roles are a reflection of our environment. They’re a reflection of the jobs that have to be done to assure our collective survival. There’s work to be done, and that need exists independently of who, exactly, is around to fill it. In our culture, tasks are often perceived as gendered: men are warriors, labourers, or good at math, and women are healers, cooks, or good with feelings. But given a shortage of mothers or fathers, men will nurture and women will hunt.

These roles came to mind as I read through The Anthropology of Childhood by David F. Lancy. The book is a broad survey of what the ethnographic record has to say about children and childhood across different cultures, and I first read it during the pandemic. I felt a deep love for my spawn but, haggard and overwhelmed with childcare, I also felt certain that we weren’t meant to spend quite so much time directly supervising them.

In his book, Lancy confirmed my biases: in non-industrialized societies, and by extension for most of our history, children spend most of their time playing with other kids, loosely supervised by their older siblings or nearby kin. As I expected, tightly choreographed playdates and enrichment activities are a malaise of our modern era (and indeed that is Lancy’s explicit thesis). However, I was surprised to also discover how our attitudes and expectations towards children, and by extension the roles adults play, are downstream of our material circumstances, of our modes of production, and vary accordingly. This feels almost trite to type out, but it wasn’t obvious to me at the time.

Consider hunting. We perceive hunting to be very male-coded but actual hunter-gatherers don’t tend to have strictly gendered divisions of labour. Hunter-gatherer societies tended to be pretty egalitarian, and at any rate hunting only provided about half of their calories. Everyone did all sorts of jobs. Of course, only some people can bear children and breastfeed them, but beyond that there simply wasn’t a lot of room for specialization. Nomadic lifestyles can’t support high population densities. After all the gathering and hunting was done, someone had to cook, and clean, and cuddle, and carry things – and there just weren’t that many “someones” around.

After a few days, once your band or tribe has exhausted all of the local foraging, and scared off the herds, it’s time to pack up, and move on to the next site. When you move around all the time, there is only so much stuff you can carry with you. That includes, well, babies. Babies are high maintenance. They spend most of their first two years of life strapped to their mothers’ bodies, which is inconvenient. For this reason, hunter-gatherers tended to have long intervals between births, and therefore lower fertility rates overall. Those who could bear children were disinclined to have more than a few.

This changed with the invention of agriculture and later, and more importantly, the invention of property rights. As a household’s survival became tied to successfully farming a plot of land, everyone’s incentives shifted. Society shifted. Farming shackled both men and women. As we began to dominate the land, we began to dominate each other.

Now, it made sense to have more children. A lot more children. The more children you can boss around, the more free labour you can extract before they become adults; even a four year old can fetch water, or watch a goat. As children became economic assets, large families became desirable. Be fruitful, and multiply.

That much child-rearing places a sharp constraint on women. Babies are high maintenance! To have ten or twelve live births is to spend twenty years or more pregnant and breastfeeding. If not stuck at home, women are forced to at least be relatively near their nursing infants. As women’s primary economic contribution declined so did their independence and relative status, and in many traditional pastoralist or farming societies women and their children are treated harshly, like chattel.

That’s the patriarchy for you.

The more tightly the lives of women are prescribed, the more rigidly gender divisions are enforced. Girls and boys are often treated differently from birth. They’re dressed differently, and they perform different chores. In many cultures, upon puberty boys are sequestered from girls, and forced to undergo painful initiation rituals whose aim is to suppress any feminine traits they may have picked up from their mothers. The work we do, the business of living, is so central to our lives that it is an important component of our identities. From an early age, boys learn to say no to “women’s work” – and yet, the gender inflection of any given task changes from society to society.

Lancy tells us that, in the Philippines, female Agta foragers hunt with bows; that on Java, in Indonesia, everyone works on the rice crop but boys and girls are responsible for different steps in its lifecycle; that for the Akwete Igbo, in Nigeria, weaving is the responsibility of women – but that among the Baulè in Cote d’Ivoire it is the exclusive domain of men.

Isn’t that interesting? Lancy doesn’t dwell on this, but I see it as evidence that the roles we perform are, to a large extent, arbitrary. They depend on your context, your culture, your modes of production. They’re fluid, they change over time, as our culture evolves, as the climate changes, as our technology improves or our access to it is degraded. For most of human history, hunter-gathering was the only option and then, a few thousand years ago, most humans became subsistence farmers or shepherds. We’re in the midst of another shift now: sociologists call it the “great demographic transition”.

This transition is over-determined, but a stylized account goes like this. The industrial revolution created a huge demand for labour in or near cities, and the invention of fertilizers and machinery greatly reduced the demand for labour on farms. At first, children were employed in factories alongside adults but improvements in automation eventually eliminated the kinds of menial tasks they were best suited for. A century ago most people lived and worked in rural areas; in rich countries today agriculture employs less than 2% of the population.

Our incentives have shifted: you can’t exploit your children like we used to. There’s no longer an upside to having large families, and at any rate we no longer live enmeshed in large kin networks with easy, free access to childcare. These days, survival in our complex service economy is understood to require long periods of education and specialization. This is an over-simplification but as women came to have smaller families, they gained greater independence, social status, and legal and political rights.

There’s still work to be done, but the material conditions that enabled this pattern of domination, and that forced certain people into certain roles have disappeared. This shift happened so rapidly that our culture is still catching up. In my family, it’s a living memory: my grandparents were born to large families, and put to work at an early age. Back then, no one thought it necessary to teach my grandmother how to read.

Life changes. Life is always changing.

A couple years after I became a father, I underwent another change.

I had experienced a profound interior shift, but to the people around me it was as if nothing had changed at all. I walked through the world with a new perspective, a different point of view. At night, I would lie awake, and think about how I could act on this revelation.

It would soon reshuffle my life.

It happened like this: one day, I took a good look at myself in the mirror. On my way out the door, I glanced at my reflection. It was the late pandemic, so I wore a mask, neatly covering my beard, and my hair, which, after two years without hair cuts draped past my shoulders, hang loose. I didn’t quite recognize the person staring back at me. Whoa, I thought, what’s her deal?, and this feels cool.

This feeling came to haunt me. It felt good. It felt really cool. The more I thought about it, the more enticing it felt. I didn’t fully understand it; I wasn’t supposed to feel this way, but I couldn’t ignore it. Before long I found myself staring, fascinated – jealous, even – at the transition timelines people posted online, blown away by how dramatically some of them had changed. The implication began to sink in.

I knew about trans people. I had queer friends in high school, and I had taken the time to question my sexuality. In my twenties, after one of my best friends transitioned, I had spent some time interrogating gender as well. The “classical” medicalized transgender narrative – feeling trapped in the wrong body – did not resonate with me, and so that was easy to rule out. But I also remember thinking that the way cis people were supposed to feel about their gender, how I was supposed to feel as a man, didn’t really make sense either.

Talking with my friends, I reasoned, if you could take a pill, and temporarily wake up as a woman, I’d try that out, who wouldn’t? Haha, given the choice I might not switch back! (I literally said this once). But those pills don’t exist, so, whatever. No big deal. Being trans was something other people did, and good for them! I did not understand their struggle, but I supported their right to exist. I concluded that, since I liked women, and since I liked my body, that was that: I was just another cishet man.

I was obviously a man. What else could I be?

I’m tall, taller than most. I have a somewhat aggressive, conflict-oriented personality. I have male-coded interests, I work in a male-dominated industry, most of my friends are men. Of course, looking back – I would not have described it this way at the time – I felt vaguely alienated from men, as a class. As a boy, I was rather bad at performing masculinity. Occasionally, my family worried that I might be gay. I was supposed to like sports, to climb trees, to rustle and tussle, but instead I was a sensitive, bookish, homebody.

It had never occurred to me that being trans was something I could do. That this was something that I could get away with, that this opportunity existed for me, too. Now that opportunity stared at me, blinking in the mirror, and suddenly my heart filled with yearning. It was possible, and that felt exciting, that felt good. I didn’t want to be trans; for months, I was scared to admit it. But whatever was going on, I had to admit that I was not cis.

I moved carefully. I took things one step at a time. I followed that feeling of joy, what felt right. I came out to my partner as non-binary, which she took in stride. I shaved my beards, and changed my pronouns. I started wearing feminine clothing, and began painting my nails. I would later go on hormones, burn off my facial hair, and change my name, but long before I took those steps, long before anyone would ever confuse me for a woman, I crossed an invisible threshold: waiting in the checkout line at the thrift store, women began to smile, and give me compliments.

I recognized that moment: I was no longer being seen as a potential threat. I was harmless now, benign even.

To transition is to take a leap of faith. In that sense, it’s not unlike having a kid: both experiences are one way doors. You can’t truly know what it’s like until after you’ve stepped through, but by then it’s too late. Once you’ve crossed over, at least for those of us pursuing medical transition, you can’t really go back to how things were before.

To transition is also to become illegible. We exist, almost by definition, at least for a while, at the intersection of what are supposedly discrete categories. We’re hard to see, we’re lurking in the background (to say nothing of how we might hide to avoid being marginalized and persecuted). Our haters use this to portray us as a recent phenomena, a malaise of our modern era, but the truth is we have always been here.

If you look carefully at the historical record you’ll find us. Which is exactly what Kit Heyam sought to do in their book Before We Were Trans, a sweeping account of gender nonconforming people across history. Certainly, the slang is new. Words like “transgender” did not enter our lexicon until the late twentieth century. But that’s also because how we think of gender and sexuality changes and shifts over time, and across cultures. The parts we play in society, the roles that are available for us, are not static. They change as our environment changes, as we continue to change.

Heyam tells us of rulers in ancient Egypt and pre-colonial Angola who were assigned female at birth but ruled as male kings; that in Queen Elizabeth’s reign gender nonconforming dress became fashionable, as male courtiers vying for the her favour adopted feminine-coded clothes and accessories; that the Japanese, during the isolationist Edo period, developed a third gender called the Wakashū – who were later suppressed during the Meiji restoration.

There is great diversity in how people experience gender, so as a historian Heyam is very careful to avoid privileging any one of the many different motivations – personal, spiritual, social, economic – that can lead someone to queer their gender, and go against the expectations that were assigned to them at birth. But reading the book I was struck by two historical examples, both rooted in military conflicts, which I thought highlighted how our environment can create these roles, and how our internal sense of self, our identities, are a negotiation with our external context, and the opportunities that are available to us.

The first is the American Civil War, for which we have evidence that at least four hundred people who were assigned female at birth enlisted as soldiers. Heyam takes great pains to point out that performing a differently-gendered task is not the same as changing one’s gender (today we accept that women can be soldiers, too), and that we will never know what was going through these people’s minds. But we do know that they really had to commit to the bit.

Consider the reality of being a soldier in 1861. These people had to endure unspeakable privations and live, eat, sleep and defecate, with no privacy, among men. If discovered, at any point, these people would be summarily discharged and prevented from serving; and so they had to look like men, behave like men, and pass as men – pass flawlessly – for the entire duration of their tour of duty. For most people, this takes conscious effort. In a very real sense, for years on end, these people became men.

Consider also the social impact the war had on their communities. The American Civil War was a totalizing conflict, and would come to involve up to a third of military-aged men in the North, and a majority of military-aged men in the South. Their society had created a great demand for men and so, in a very real sense, men stepped up to fill it.

The other example happened during the First World War. At the beginning of the war, the British government rounded up every military-aged man living in the United Kingdom who was also a citizen of an enemy country, and imprisoned them. Most of them – around 20,000 – were sent to the Isle of Man (yes, really), and forced to live in a shambolic interment camp built for this purpose.

Overnight, this created a very weird place. The camp was a crowded and stressful environment, with little privacy, and to avoid going crazy from inactivity the camp internees became highly organized. Before long, the camp featured sports leagues, educational classes, newspapers and orchestras. But the centre of life in the camp, the activity that most allowed them to escape their harsh circumstance, was the theatre. At its peak, the Knockaloe Interment Camp had a bustling scene, with twenty theatres. By the time it closed, internees had performed over 1,500 shows, and hundreds had worked as actors, stagehands, technicians, and costume-makers.

A lot of plays had female parts, so they had to make do. In theatre, this is not unusual; historically, women were often banned from being performers. The men sewed dresses, and improvised wigs, and every night stepped on the stage and played women. They played women not for comedic effect, but seriously, intentionally: they sought to play women convincingly.

After a while, a funny thing started to happen: at the end of the night, when the show was over, some of the actors kept wearing dresses, and wigs, and female names. They started living full-time as women – and the camp accepted them as such. They were referred to by female names, they attracted performance reviews that treated them as women, and received fan mail and devoted followers that saw them as women.

In doing so, the camp stopped being an “all-male” environment. Which, judging by the letters and diaries that have survived, seems to have been important for everybody. With all the isolation and confinement of their interment, having women around provided a sense of normalcy. The camp’s theatres needed someone to play female roles, and to do so convincingly, and so did the camp as a whole, to help safeguard everyone’s mental health.

Their society, as it were, had a great demand for women – and so women stepped up to play the part.

These stories resonated with me. Growing up, I had spent a lot of time trying to be tougher, to show the world my sharp spiky quills. It was only after I saw that I had the opportunity, that I understood that I too could play this part, that I realized that I might want to live differently. That I wanted to care more, to show the world my soft underbelly instead.

I just could not conceive of it. It kind of… wasn’t an option, back when I was a teenager. How we think of gender and sexuality are always shifting; words and concepts like “non-binary” were not available to me twenty years ago. You either had a deep-seated conviction that something was terribly wrong, or you didn’t. There was no in between. There was no room for the idea that I might not hate being masculine, but experience far more joy presenting feminine.

My mental model of the world did not include this as an option.

Our mental models are cognitive tools. We need them. They’re necessary simplifications of the real world. All models are wrong, but some are useful. A good model can be used to improve our understanding, and make accurate predictions. A bad model, though, can prevent you from seeing the world as it really is. Our ideas about the world can be so deeply rooted that they can blind us from seeing what is right in front of our nose.

This can sound abstract, or loftily high-minded, but excessively wrong models can have disastrous consequences. When we encounter something in the real world that doesn’t fit mental our model, humans often find it easier to to change reality than the ideas in our heads.

Take sex, for example. We’re taught that sex, biological sex, is a binary with two clear and unequivocal categories. Some people produce big gametes, others produce little gametes, and that’s it, the end. Except… that’s not the whole story.

In reality, sex is more like a spectrum with a bimodal distribution. The closer we look, the fuzzier the boundary between categories gets. Some people really do have a combination of sexual characteristics, and today we use the label “intersex” to describe them. There are dozens of different developmental pathways that can lead to someone having intersex traits.

Sometimes this manifests as ambiguous genitalia, and is immediately obvious. Sometimes, this only becomes apparent at puberty, when a person begins developing secondary sexual characteristics that don’t match an assumption made at birth. Some people produce children and live most of their lives before accidentally discovering, in late middle age, that they have an atypical complement of gonads. If you’ve never been karyotyped, you might never know for sure.

Unfortunately, the history of intersex people is one of intense stigma, discrimination, and violence. Medical professionals have a long and sordid history of mutilating intersex children that did not match their mental model of the world. Sometimes in the name of curiosity, but more often as part of an effort to force their bodies to conform, intersex children have been and continue to be subjected to medically unnecessary surgeries, without their consent, that are intended to remove “excess” tissue, or to correct a “disorder”.

These days, people are often encouraged to imagine gender as a spectrum. Cartoonishly, you could picture an axis with two arrows pointing in opposite directions. At one end, there is Yosemite Sam, and at the other Jessica Rabbit, resplendent in high femme glamour. In this model, you could imagine a steady progression of genders, as femme leads to butch, butch leads to twink, twink leads to bear, and so on. However, the butchiest butch is more masculine than the twinkiest twink; the term “high femme” implies the existence of “low femme”. We can improve this model.

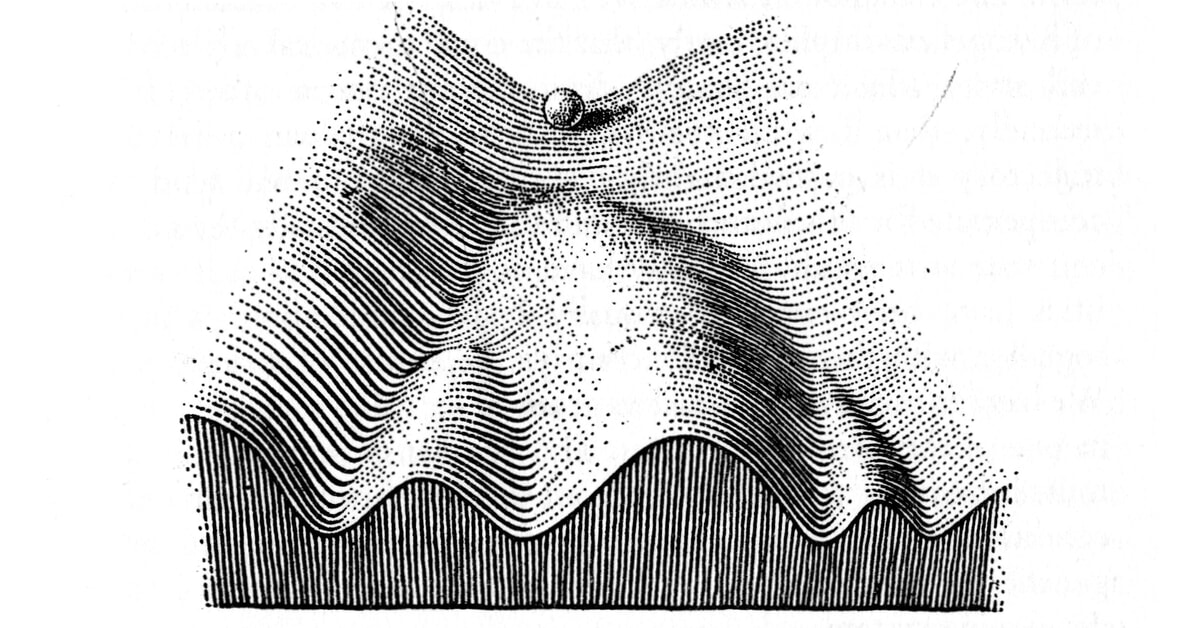

By contrast, I like to think of gender as a vector in high dimensional space. Imagine that you could encode the totality of someone’s presentation – the shape and abilities of their body, how they dress and behave, how they are seen by others, how they would like to be seen – as an n-tuple, and that we could plot everyone’s presentation. These points would cluster in particular places. If we drew a line around these clusters, and folded it into something we could perceive, the manifolds might look like mountainous ranges with peaks and valleys.

Gender consists of this landscape. As we grow up, and we age, and we change, we traverse it. Think of it like hiking down a mountain. It’s not a linear process. You can get trapped in local minima; sometimes you have to gain altitude in order to keep descending. The journey between two peaks may seem distant, and far apart, but they’re actually only separated by a narrow gap. All it takes is a leap of faith.

I hope that makes sense; I know it’s a bad model.

The way I see it, everyone transitions. Everyone is transitioning. Everyone experiences different genders, or forms or stages of gender. We’re all moving through different roles. We are all on a journey. Some of us roll downhill, and some of us don’t mind going for a long hike.

The only constant is change, and all of us are always changing, all of the time. This is a cliché, but it’s true. To live is to change, for only death is immutable. You are not the man your wife married all those years ago (that guy had more hair). Your closet is full of clothes you don’t (or can’t) wear anymore. You used to stay up all night, and these days you like to be in bed by ten. You’re a soccer mom now. You got a haircut. You got swole. You changed your name.

Yesterday you were a baby, and tomorrow you will be a babushka.